The Chinese Cookbook Project IV: From the Best Chinese Restaurant in the World

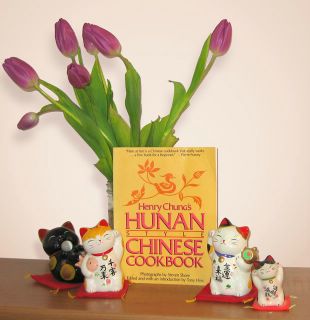

One of the few cookbooks featuring the cuisine of Hunan province, Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook is sadly out of print.

In 1974, Tony Hiss, a staff writer for The New Yorker Magazine, dubbed Henry’s Hunan Restaurant on Kearny Street in San Francisco’s Chinatown, “the best Chinese restaurant in the world.” Thirty-two years later, though the original tiny thirty-six seat establishment is long gone, four other branches of Henry’s Hunan are still family owned and operated and going strong, with a huge following of San Francisco natives and tourists. Their dishes are still considered to be among the most authentic and flavorful Hunanese foods available anywhere in the world, and people are still eating and raving about farmhouse classics such as Harvest Pork and Smoked Ham.

In 1974, few people may have ever heard of Hunanese cuisine, but in 2005, an informal survey of Chinese restaurants in the US reveals that Hunan cooking is one of the most popular of the Chinese regional styles, with many restaurants using Hunan in their names. Even if a restaurant’s typical style is Cantonese, there is bound to be at least one or two classical Hunan dishes on the menu to satisfy customers who like fiery dishes.

Oddly, though Hunan cookery is very popular among eaters in the United States, there are few cookbooks available to help intrepid cooks replicate these flavors at home. The closest many home cooks can come to finding Hunanese recipes in print are recipes sprinkled hither and yon throughout many general Chinese cookbooks.

The only cookbooks to feature Hunanese cookery exclusively seem to be out of print. (I have heard it rumored that Fuchsia Dunlop, author of the seminal Sichuan cookbook, Land of Plenty, is currently researching a similar work on the food of Hunan province; I hope this rumor is true, as there is a real dearth of documentation in English of Hunanese food.) Of the three of them I own, the best is unsurprisingly, Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook.

An unpretentious little volume, with a glowing introduction by Tony Hiss, photographs by Steven Shore and an amazing amount of historical and cultural information, Henry Chung’s cookbook is a powerhouse of authentic Hunan recipes. Many of the dishes for which his restaurants are justly famous are featured within these pages, but there are many other great recipes on offer as well, including a delicious sounding chicken, ham and mushroom soup which Chung claims was given to women to help them recuperate after childbirth.

The story behind each dish is outlined before the recipe, and each chapter is illuminated by personal remembrances of Chung’s years growing up. He paints a vivid portrait of his grandmother, who he declares was the dominant personality in his family and who taught him everything he knew about cooking. A devout Buddhist, Chung’s grandmother was also well known as a great cook and a very generous, loving person. She apparently treated all beings with honor and respect, from Chung’s childhood dog (when he died, she gave the dog a Buddhist ceremony in order that he might reincarnate as a man in the next life) to beggars to family and friends. From her, Chung says he learned not only how to be a great cook, but how to be a good person.

Hunan province is apparently well known for its folklore, and Chung includes a few pages of folk traditions regarding marriage, cooking, Feng Shui and one interesting entry called, “How to Model a Baby Before Its Coming into Being.” Here, Chung lists traditional advice about how to go about the peril-fraught business of conceiving a healthy, lucky child.

The recipes are all well-written, with a lot of advice on substitutions and clear photographic illustrations for the complete beginner. General instructions on how to improvise a steamer, how to handle Chinese cooking utensils and how to cut ingredients uniformly are also written and illustrated in a clear, concise fashion.

Since Chung claims Kung Pao Chicken as a Hunanese dish in the book, I decided to try his recipe for it. However, as I had no chicken and instead had beef, I used his recipe for Kung Pao Thin-Sliced Beef with Roasted Peanuts.

I did change two things about the recipe. One, he had the cook deep fry the beef in two cups of oil, then drain away all but a few tablespoons in order to stir fry the rest of the dish. Not only is this a messy prospect, I don’t like adding a million and a half calories to my dinner from deep frying it when I could just as easily and flavorfully stir fry it from the beginning. So, out went the two cups of oil before I even started cooking.

Also, his recipe called for one cup of canned sliced bamboo shoots, or one cup of sliced carrots or one cup of sliced asparagus. As I had fresh water chestnuts, gai lan and carrots, I used all three instead.

However, the seasonings and general directions are the same as they appear in the Chung book.

Henry Chung’s Kung Pao Thin-Sliced Beef with Roasted Peanuts

(The original text is in brown, my substitutions are in green.)

Ingredients:

1/2 pound flank steak, cut across the grain into pieces about 1/8″ thick and 1″ long

1 egg white or 1/2 tablespoon cornstarch (I went with the cornstarch, as I was nearly out of eggs)

1/2 tablespoon white wine (grape wine is rare in China, I substituted white rice wine)

2 cups vegetable oil (I used 3 tablespoons peanut oil)

5 whole dried hot red peppers

1 cup canned sliced bamboo shoots (I used a total of 1 1/2 cups of vegetables, made up of fresh water chestnuts peeled and sliced into rectangles, 4 stalks of gai lan, cut on the bias 1″ long, and baby carrots, cut on the bias)

1 teaspoon hot red pepper powder, or 1 teaspoon hot red pepper sauce or hot pepper oil (I used my own homemade hot pepper oil with the seeds included)

1 tablespoon fresh garlic, minced, optional (garlic is never optional at my house)

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon white wine (again, this was substituted with rice wine)

1/4 tablespoon sugar, optional (I left that out, but should have put it in)

2 scallions, both green and white parts, cut into 1 1/2″ long pieces

pinch salt

1/2 cup roasted peanuts, crispy and fresh (I used unsalted dry roasted peanuts)

1/2 teaspoon sesame oil, optional (I bet you will not be surprised to hear that sesame oil is not optional in my kitchen, either)

Method:

Mix the beef with the marinade, and allow to stand for five minutes.

Heat a wok over highest heat for 2 minutes; add vegetable oil. As soon as oil is smoking hot, vigorously stir-fry the beef pieces for 5- 10 seconds only. Do not cook longer. Remove beef to a strainer to allow oil to drain off. (I would use a wire skimmer to do this if I were going to do it and put it on a platter lined with layers of paper towels to absorb the oil. If I were to do this, which I am not likely to.)

Pour all but 2 or 3 tablespoons of oil from wok and heat until smoking hot. Fry the hot red peppers until dark brown, about five seconds. Add bamboo shoots, hot red pepper powder, and garlic, stir fry for 1 minute. (Okay, here is where I changed the recipe the most. I skipped the deep frying part entirely, and went to the 2-3 tablespoons of oil business. I fried the chiles until dark brown, then added the meat, the chile oil and stir fried until the meat was brown, then added the garlic, and kept frying. Then, I added the vegetables, all at once; I had cut them so that they would cook at the same time, approximately.)

Return beef to wok and add soy sauce, wine sugar, scallions, salt and roasted peanuts. Stir fry vigorously until thoroughly blended and hot for about ten seconds. Remove to serving plate and garnish with sesame oil. Serve with steamed rice. (Okay, after I added the vegetables, I added the soy sauce–I used Kimlan Aged Soy Sauce–wine, scallions, salt and peanuts. And I stirred until it all came together and was done.)

Kung Pao Beef from a recipe I found in Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook.

My feeling, and Zak’s, was that it was good, but not quite spicy enough, leading me to believe that the quantities of chile called for in the book as written was scaled down for American tastes. Which is fine; it just helps to know that when you are cooking from it. If I were to do this recipe again, I would at least double the amount of chile oil, and I might add fresh chile peppers to it.

I think on the whole, that while this was a perfectly good rendition, I prefer the Sichuan take on Kung Pao, which includes Sichuan peppercorns and ginger, as well as the ingredients featured in the Hunan version. I prefer the more complex flavors featured in Sichuan cookery, and I like the wild interplay of various ingredients that set the tongue ablaze.

I will try some other recipes in this book at a later date, and when I do, I will post about them–several of them sound delectable. I just happened to have the ingredients for Kung Pao on hand and was curious to try Chung’s version and compare it to the way I make it which is a distillation from my experiences tasting the dish made by various chefs and my experimentation with many recipes I have tried over the years.

I am especially eager to try Harvest Pork and Stir-Fried Duck with Bitter Melon, which Chung claims is a very local dish served only in his home county of Li-ling in Hunan. I will have to give it a shot in the summer, as Chung notes that both bitter melon and duck are cooling.

3 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

Hey Barbara,

I love your reviews on these cookbooks. How did you find them? Thanks for sharing!

Comment by Anonymous — March 7, 2005 #

Ops, it was me – Shirley – in the earlier posts.

Comment by Anonymous — March 7, 2005 #

Hey, Shirley!

I get most of them on ebay and Amazon.com’s used books, though I look on bookfinder.com as well. How do I know what to look for? Well, that is another matter entirely–I ask around to friends on eatingchinese.org, I asked Grace Young, and I ask other Chinese cooking teachers. I looked up the library catalogues for the two largest Chinese cookbook collections, and copied titles there and searched for them on the internet. Sometimes, I just search on ebay and see what is available and learn about titles that way.

And, I comb used bookstores. And it is amazing what I can find.

But I have been very lucky in my ebay and Amazon purchases. Often, I have managed to aquire quite rare books which generally go for very high prices very inexpensively. I’ve also scored some signed copies of books, as well, for incredibly low prices.

Comment by Barbara Fisher — March 7, 2005 #