What To Eat When You Read About Curry

It is all the fault of this book I am reading, you see.

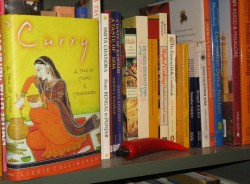

Entitled, Curry: A Tale of Cooks & Conquerors, by Lizzie Collingham, it is a history of the development of the dish known as curry. (Who would have guessed?)

It is also utterly engrossing, at least to a food geek like myself who finds the development of cuisines to be fascinating. I had known much about the Persian influence upon northern Indian cusine, and of course, I knew that it was in the port of Goa that the Portuguese brought the chile pepper from the New World to India where it then spread over the south like a wildfire. But, I really didn’t know that much about the British influence upon Indian food–I knew more about it from the other way around: the Indian influence upon British food. So this book is keeping me occupied, all through the day and night. (Look for a review of it when I am done.)

It is also making me hungry.

So, I am reading it, and it is talking about the Mogul emperors in the north of India, and how they brought the Persian way of cooking rice to India, and brought the taste for using lots of dairy products, fruits, nuts and meat in the cooking, and I thought to myself, “Oh, I need me some of that.”

And then, I got to the next chapter which was all about the cooking of the south of India, and how when the Portuguese brought the chile pepper, everyone was using it in everything along with mustard seeds, ginger and cumin and I said, “Oh, damn. I need some of that, too.”

So, I put down the book, went to the kitchen, dug around, then headed off to the grocery store and picked up a few things.

Because I had to have curry. I just had to. Had to, had to, had to–because there is nothing worse than reading about all of these delectable dishes and not being able to taste any of them.

So I fixed up two dishes, plus some turmeric-scented basmati rice: one to represent the northern, Persian influenced style of the Mogul empire, and the other to stand up for the fiery, intense vegetarian foods of the south.

I decided on lamb kofta in a yogurt sauce with pomegranate and mint, and aloo gobi.

Ah, aloo gobi. It had been too long since I had eaten it.

Aloo gobi is quite simply potatoes cooked with cauliflower in a turmeric-colored, very thick curry sauce. Many versions of it that I have eaten in restaurants that cook primarily northern Indian food have been quite tame, but my favorites have been the ones that are redolent of mustard and cumin seed, snapping with fresh ginger and browned onions and filled with the fire of many fresh chiles.The sauce is not plentiful, but is very strongly flavored, and clings tightly to the potato chunks and cauliflower florets.

It is one of my favorite “classic” curries, and is one that I have never made before, mainly because I could always get it in local Indian restaurants.

As that is no longer the case, here I am, book in hand, hankering for a bowl of aloo gobi and no great Indian restaurant within an hour’s drive.

What else is a woman to do but grab the cauliflower by the head and make it into a curry?

Did I use a recipe?

No. I have to admit that I did not–I just remembered what the great chef at Akbar in Maryland put in his, and followed suit. He was from Dehli, mind you–in the north, but one of the waiters told me that he had also spent time cooking in Hyderabad, in the south-central part of India, and so had picked up the southern ways with chiles, mustard oil, mustard seeds and fenugreek greens.That was what made his food so good, I think–just when you thought he was just an amazingly proficient chef in the complex court dishes of the Mogul empire, he would turn around and make a steaming platter of aloo methi–potatoes fried with fresh ginger, chiles, ground spices and bittersweet fresh fenugreek green that exploded with the flavors of southern India from the first bite.

I didn’t use a recipe for the kofta, either, to be honest. At this point, I just work instinctively with Indian spices, and only use recipes for bread or for dishes that I am not familiar with. For the kofta, I went with a basic kofta recipe, similar to my saag kofta, and changed the spices to reflect a less spicy, more sweetened flavor. I also added pomegranate molasses to the meat mixture and the sauce, in order to bring that sweet-sour fruit flavor that I wanted to highlight in honor of the Persians, who brought pomegranates to India. I also removed the turmeric and paprika that are used to color the yogurt-based sauce for the kofta; very much wanted the dish to contrast with the highly spiced brilliant yellow, hot aloo gobi.

One more note about the potatoes before I go to the recipes: most Indians would peel thier potatoes, so to be authentic, you should, too. However, I had some very pretty, very young, tender fingerling potatoes, both red and white, in the house, and those are the ones I used. I just scrubbed their baby skins until they were squeaky-clean, and cut them into sixths or quarters, and used them that way. Their waxy texture suited the dish admirably–they kept their shape and the creaminess of their flesh contrasted with the crisp-tender cauliflower. You can use whatever potato you want, but remember that the waxy ones will hold their shape and have a delightful texture. I tend to use the mealier potatoes for fried dishes like pakora or aloo methi.

After the first bite, Zak and Morganna declared that reading the history of curry was good for me and that I should do it more often.

I am sure that their enthusiasm for my reading material was not in the least bit self-serving.

Ingredients:

8 small fingerling potatoes, well scrubbed and cut into quarters or sixths, depending on size

pinch salt

1/2 head cauliflower, cut into florets about the size of the potato chunks

pinch salt

2 tablespoons mustard oil or peanut oil

1 small onion, sliced thinly

1 1/2″ cube fresh young ginger, peeled and cut into very thin slivers

2 ripe jalapenos, sliced thinly (or to taste)

1/2 teaspoon whole cumin seeds

1 teaspoon mustard seeds

salt to taste (about 1/2 teaspoon)

Masala Ingredients:

1/4 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

generous pinch asafoetida/hing powder

1/2 teaspoon turmeric

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

1 1/2 teaspoon coriander seeds

1/2 teaspoon black peppercorns

1 handful fresh cilantro leaves, roughly chopped

wedges of lime

Method:

In two separate pots of appropriate size, just cover potatoes and cauliflower with water salted with just a pinch of salt, and bring to a boil. Cook cauliflower until it just begins to soften, then drain and set aside. Cook potatoes until they are halfway soft, turn off water, but do not drain.

Grind the masala mixture into a fine powder.

While the potatos and cauliflower are parboiling, heat oil in a skillet or saute pan and add onions. Cook, stirring, until they are half-browned–a dark reddish gold color–then add the ginger and 2/3 of the chile. (Reserve the rest for garnish.) Keep cooking for another minute, add whole cumin and mustard seeds and continue cooking until the cumin seeds darken, the mustard seeds start popping, and the onions are a deep reddish brown. It will all be very, very fragrant. Add the masala powder and keep stirring, cooking until the powder toasts slightly–about one more minute.

Add the potatoes and their cooking water, and the cauliflower. Stir to combine. Bring to a brisk simmer. If there isn’t enough water, add some more to just cover all ingredients. Add salt to taste.

Allow to simmer down until there is barely any sauce, and what is there clings tightly to the potatoes and cauliflower florets.

Stir in reserved chiles and cilantro and serve with lime wedges–the shot of sour really makes the spices sparkle.

Pomegranate Kofta

To make the pomegranate kofta, follow my instructions for saag kofta, but make the following changes:

1. Leave out the collard greens altogether. Instead, remove the seeds from a medium pomegranate and set aside.

2. For the curry paste, use the following spices, and follow the directions in the recipe for saag kofta: 1/2″ cube fresh ginger, 3 cloves garlic, 1/4 teaspoon dried chile flakes, 1 teaspoon cumin seed, 1/2 teaspoon fennel seeds, 1/2 teaspoon cardamom seeds, 3 whole cloves, 1 black cardamom pod, 1/2 teaspoon black peppercorns, 1/2 teaspoon salt, 1/2 teaspoon pomegranate molasses.

3. For the sauce, follow the directions and ingredients for saag kofta, except make these changes and omissions: no paprika or turmeric, and add 1 teaspoon pomegranate molasses with the cream.

Serve with a generous handful of pomegranate seeds and minced mint leaves sprinkled over the kofta.

12 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

I will definitly mak Aloo gobi! And I’m looking forward to the review!

Comment by ilva — February 2, 2006 #

I don’t think the claim, that Portugese introduced chillies to India is true, Barbara. Western writers and Christian monks have a long history of making false claims about things like these, to promote their agenda and their culture/country’s importance.

I so wish the books written by our ancestors were preserved, that’d make it easy, for people like me to prove these claims for what they are. Until then, or even then, sorry I have to say this, but the propaganda continues.

Comment by Indira — February 2, 2006 #

wow Barbara, your Alu Gobi recipe is very close to the authentic. Kudos for not using a recipe! I really don’t like Alu Gobi at all and find it surprising when so many people out here simply love it!!

hehehe, but kofta, now that’s something I can’t live without!! :o)

Comment by Meena — February 2, 2006 #

I know that there are those who say that chiles originated in India–in fact, that claim is made not only by Indians, but Europeans.

However, biologically speaking–the chile is from the New World. It was grown by the Aztecs and Mayans, cultivated from the wild chiltepen chile which has pods the size of baby’s fingernails.

The reason chiles are called chile peppers is because Columbus thought he had reached India when he landed in the West Indies and found the Arawaks eating food made fiery with chiles. So, he called the islands the Indies, the Arawaks Indians, and even though chiles look nothing like the black pepper and long pepper he sought, he called them peppers, and brought them back claiming to have found the sea-route to India.

Well, as we all know, the wayward Genoan did no such thing, but the chile was brought to Spain, and from there, spread in use to Portugal, Hungary and elsewhere through Europe. In Hungary, it became paprika, and became a signiture ingredient in their cuisine. (At the same time, tomatoes, which had been unknown in Italy before that time, and potatoes, which had been nowhere near Ireland or Germany, began making inroads into Europe, completely changing the way people ate in those lands forever.)

Chiles came to both China and Italy via the Portuguese traders who sought to take the spice and silk trade from the Arabs. Before that time there is no written record of anything hotter than ginger and black pepper in any of the extensive culinary or medical literature of either country. (The Indians and Chinese both having had a head start on civilization from the Europeans, and thus having developed advance cultures with writing way before the Europeans got their acts together and did the same.)

Botanically and historically speaking–the chiles of India and China are the same plants as the chiles of the New World. That isn’t European chauvinism speaking, or even propoganda–but science. (I have read the same from Indian authors–Monisha Baradwaj and K.T. Achaya, for two examples–Achaya, being the more scholarly.)

Besides–the Portuguese cannot claim to have invented the chiles–they merely took the very useful plant from one part of the world to another–and from there, it spread. They didn’t even discover it–the natives of South America and Mexico did that! Nor did they bring them to Europe–that would be Columbus and his Italian and Spanish sailors who did that.

What I find most interesting as I read about the history of food–and I don’t just mean this book, but all the research I have done on it, is how quickly foodstuffs will travel from place to place and cooking styles and cuisines will change in a fairly rapid manner. It is hard to say what is the native cuisine of any one place in the world. We think of tomatoes as being intrinsic to Italian food, but they did not come to Italy until the late Rennaisance period, and were not extensively adopted until later than that.

We think of potatoes as Irish, chocolate as Swiss and chiles as Chinese or Indian, but all of these foods, in addition to corn, certain beans, and many squashes, but they came from the Americas–and they changed the way the world ate forever after.

To me, there is no propoganda there. There is no real claim that European colonials can make over these foods–they were developed by the natives of the Americas–who were originally from Asia, btw. The only claim they can make is that they transported them from here to there as they quested for land, money and power in their expansionist empire building periods. But chiles, tomatoes, potatoes and all the others were not “thiers” to claim–so I don’t really see it as propoganda.

I can see how it can be viewed that way, though. White folks have a habit of making big of themselves and being self-aggrandizing twits when it comes to writing down history. In this case, however, what I am finding is that for all the British seemed to want to change Indian cuisine–the Indians did more to change British cuisine and food preferences than the other way around. (Which is how I had always learned it–what I am finding though, is the extent to which these changes in British food habits and tastes were made and how early they were made.

While I think that there is definately colonialist propoganda written by Westerners on subjects relating to India and Indian foods, I don’t think that this book is one of them, Indira. I will write more about this when I do the review–and I will quote Indian authors on the chile pepper in India.

Thanks for keeping me on my toes, sister!

I’ll write more about it in the review of the book.

Comment by Barbara — February 2, 2006 #

Ilva–look for the review later this week or early next week.

Meena–I think that Americans love aloo gobi because it involves potatoes. Potatoes are a staple food here, and most Americans grow up eating them in some way, shape or form. Everyone in my family cooked them as the main starch along with bread.

Of course, when I was growing up my main love for starch was rice! I had a passion for it and wanted it all the time–my Chinese friends tease me and say that is because in my last life I was a Chinese person and so I wanted that which was most familiar to me!

Back to potatoes: Americans love them, so any dish that contains them is going to attract our attention.

My very favorite vegetable based Indian dishes, however, do not involve potatoes. Baigan Bartha–I could eat gallons of that, I think, and bindi–I don’t know what the dish is called, but I love okra cooked with mustard seeds, mustard oil, turmeric, pepper and onions, or okra cooked with tomato, ginger, black pepper and chile. I adore those dishes, but I don’t make them here because neither Zak nor Morganna would eat them.

Comment by Barbara — February 2, 2006 #

Oh Barb!! You made think of Baingan Bharta now! That’s my all time favourite veggie and like you, I too can eat gallons of it! I really miss the way my mom cooks it. Here at home, I have the electric stove and have to make use to the broiler to burn my eggplants. Can’t wait for summer, when we have fire-grill BBQs and I can burn a truckload of eggplants!!

I’ve okra in my fridge and plan to make it for dinner tonight. I’ll post the recipe especially for you sometime this week!

Take care!

Comment by Meena — February 2, 2006 #

Oh, yes! Grilled eggplant is best for baigan bartha! I will cut it thinly and saute it for the dish, but the smokiness is best.

Have you ever had baba ganoush? It is a Turkish/Arabic/Lebanese dish that uses fire roasted eggplant pureed with garlic, sesame paste and pomegranate molasses or lemon juice. It is so delicious! (There is a recipe for it here under Middle Eastern Recipes….)

Comment by Barbara — February 2, 2006 #

Oh Barbara, now I need ME some of that. The book AND the food!

Comment by Meg — February 3, 2006 #

Hey, Meg–what I am finding so fascinating about the book is how much the experience of living in India changed the British. It is a period of history I knew little about–I mean, other than the basics, the British East India Company’s private army was the largest standing military in the world at the time, and the Brits were being imperialist cretins, but that was about it.

What I never realized was the extent to which British tastes were changed–and not just food tastes, but tastes in clothing and ornament–by the experience of India. Even people who had never gone to India started eating more highly spiced foods because of the influence of people who had gone and returned.

The roots of Chicken Tikka Masala being recently named as the favorite dish in the UK truly go very deep.

Comment by Barbara — February 3, 2006 #

I swear you’re topping the NYTimes at every food corner!

I want to read this book at some point (i.e. when my chinese classes are taking up all my precious food time)and review it too since my background in cultural history relates to a read like this one.

Understanding how dishes develop make creating them in your kitchen even more wonderful (plus, you get to show off to your family all your new found knowledge!).

Comment by Rose — February 3, 2006 #

Thanks, Rose! I will try not to be too smug about it scooping the NY Times twice, now.

Maybe they should hire me? 😉

I am really into the development of foods, recipes and culinary history. It is a thing. Since I am all about history anyway (I minored in it in college, and nearly went for an MA in it–and may yet), it should come as no surprise that I love to read about food history.

But it makes sense–food is not just sustainance–it is a carrier of culture. It is part of how humans define themselves, it is part of how we identify ourselves socially. It is part of who we are as a people–so of course, we can use food to trace the development of cultures, or use the culture to trace the development of foodstuffs.

It is a two-way, reflexive process.

Okay–enough food geeking now.

Comment by Barbara — February 3, 2006 #

Barbara — I loved the book and recently bought myself a copy.

I know you (kind of) through Indira’s blog.

Do you like the Mulligatawny — today I am going yet another variation on it..

Appla rasam.

Check out this food article if you have the time..

http://www.csmonitor.com/2006/1011/p18s03-hfes.html

Comment by tilo — January 12, 2007 #