Chinese Wheat Noodles 101

Italy and China have been metaphorically duking it out over which country is the birthplace to the ubiquitous noodle.

Archaeologists can confidently say that noodles as a foodstuff originated in China; recently a noodle excavated inside an overturned pot near the Yellow River was carbon-dated to approximately 4,000 years ago.

That is an old noodle, far older than any noodles which have been found in Italy.

Interestingly however, it is a noodle not made of wheat. It was made from millet, the first prevalent staple grain crop of China.

But really, it doesn’t much matter to me where noodles were first made. I never met a noodle I didn’t like, whether it was from Italy, China, or my grandmother’s kitchen in West Virginia. They are all good, soul-satisfying foods, versatile and chameleon-like, which can be both simple and elegant in presentation and flavor.

Types of Wheat Noodles

Wheat noodles are now common all over China, although they originated in the northern provinces where wheat is grown in preference to rice which cannot survive the cold winters of that region. Generally speaking, Chinese wheat noodles can be divided into two broad classes: plain noodles which consist of wheat, water and salt, and egg noodles which are made from wheat, water, salt, eggs and perhaps other ingredients. Both types are available fresh (or frozen) and dried in the marketplace, and whichever one is used depends on the recipe and the taste of the cook who is presiding over the stove.

While it is traditional to use one or the other in certain recipes, most cookbooks and cooks I personally know will freely substitute one type of wheat noodle for the other in any given dish, depending on personal preference and what they have in their pantry at a given time.

Plain noodles are a good basic noodle to have in the pantry or freezer to use in soups, cold noodle dishes and stir fried noodle dishes. They are creamy or greyish white in color, and cook up to a soft ivory color. Whether fresh or dried, they tend to cook quite quickly, so it is best to avoid overcooking them. They have a subtle, nutty sweetness of their own, but mostly, they serve as a neutral base upon which other flavors can be easily built.

The only ingredients in plain noodles should be flour, water and salt, though some fresh and frozen noodles also have sodium benzoate added as a preservative. Almost all Chinese noodles are made with salt in them so their cooking water does not need to be salted to flavor the noodles. It is already present and accounted for in the noodles themselves. They are packaged either straight in boxes or bags, or, more often, coiled together into little nests which represent a convenient serving size, which varies according to the width of the noodle. The fresh ones are very long and are coiled into bundles which are then either vacuum packed or wrapped in cellophane or plastic bags.

I have no particularly favored brand of dried plain noodles, but I have found that the company called

“Twin Marquis” makes very good fresh plain noodles which are equally good after being frozen. I have successfully used their fresh noodles in making lo mein, (stir-fried noodles) and cold noodle dishes when I wanted a chewier, more substantial texture than a plain dried noodle would give me. Their noodles are square in cross section and are comparable in width to thick spaghetti.

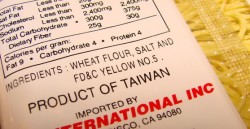

Egg noodles are generally a pale yellow in color from the egg yolks. The richness of the eggs give flavor and a meltingly tender quality to the noodles, but it behooves the clever cook to carefully examine the ingredients list of any yellow noodles with care. Some lower-quality noodle companies make yellow noodles that are colored with food dyes to simulate the more expensive egg noodles, and will charge a higher price because of it. These yellow noodles will have the same texture of plain Chinese wheat noodles, and are not worth even a few pennies more than plain white wheat noodles.

Egg noodles are widely available both fresh (or frozen) and dried, in a wide variety of widths and lengths. They are used in soups, cold noodle dishes, as stir-fried noodles and as pan-fried noodle pancakes, as well as deep fried noodles. They are delicious, and are well worth the few extra pennies more in cost to use regularly, though I do tend to keep a wide selection of both plain and egg noodles in my pantry and freezer so that if I get the urge to make any particular noodle dish, it is likely that I have any noodle necessary for the job. Like plain wheat noodles, egg noodles are often packed in nest-like bundles or in straight packages when dried and are available coiled into neat bundles when fresh.

Some egg noodles are also flavored with shrimp roe or colored and flavored with spinach. The shrimp noodles are a dark salmon-tinted tan, while the spinach noodles tend to be a soft sage green in color. Beware of bright mint green noodles–check the label–they usually are nothing more than plain noodles colored with food dye! These special egg noodles are often used in appetizer dishes and with soups, where they add color and subtle flavor to the bowl.

Once again, I am very fond of the fresh egg noodles from Twin Marquis, which I can find both in the refrigerated section and the freezer case of most local Asian markets. Nasoya Chinese Style Egg Noodles are widely available in most American supermarkets in the refrigerator section where tofu and vegetarian meat substitutes are sold. I used them the other night in making cold sesame noodles, and found that they turned out as well as a batch I made with some Twin Marquis noodles. The added bonus is that they are very easy to find and they have more explicit cooking instructions on the package than are available on the packages of most Chinese made noodles. (Though my method for boiling noodles is even better than what Nasoya suggests on their package.)

Italian Pasta vs. Chinese Noodles

Unlike Italian pastas which come in a dizzying array of often fanciful shapes and sizes, Chinese noodles, both plain and egg, are most often straight or curly and long. Their shapes in cross-section are round, square or rectangular, with thicknesses ranging from nearly hair-fine to as wide as a woman’s thumb. While it is true that there are traditional pastas which are handmade and molded into different creative shapes with fingers, most commercially available Chinese noodles look similar to Italian spaghetti, angel hair, linguine and fettuccine.

Speaking of Italian pastas, many cookbooks recommend that a cook substitute a similarly shaped Italian pasta if Chinese noodles are unavailable.

I disagree vehemently with this advice. First of all, decent wheat-based Chinese noodles are increasingly available in American grocery stores, and even in small towns and medium sized cities, there are Asian markets. If all else fails, one can order any Chinese ingredient one cannot find in town from Internet-based businesses, usually for very reasonable prices and moderate shipping costs.

Secondly, and most importantly, I disagree with the advice to substitute Italian pasta for similar-sized Chinese noodles on the grounds that the texture will be all wrong. Chinese noodles, even the dried ones, are softer and more tender than dried Italian pastas. This is because the types of wheat used to make these products are totally different. The wheat used to make Italian dried pastas is very hard, among the wheat types with the hardest kernels. These kernels are ground coarsely into a yellow-grainy flour called semolina, which is then used to make machine-made dried pasta which cooks up to a noodle with a very distinctive chewy quality.

Chinese noodles are made with wheat with softer kernels, after they are ground into a silky-smooth flour. Whether made by hand or machine, these noodles, while fairly sturdy, are more brittle than Italian pasta, and should be handled a bit more carefully. They cook much more quickly than Italian pasta, which is why I suggest a simple boiling method below to use in order to avoid overcooking Chinese noodles.

The only Italian style pasta I have ever managed to successfully substitute for Chinese noodles, are the hand-made soft wheat Northern Italian style noodles made by Rossi Pasta. These noodles are made from softer wheat than machine made noodles, much in the same way that Marcella Hazan describes as being typical of northern Italian handmade noodles. Semolina is never used in home made pasta in the north of Italy; instead, Hazan says that a flour similar to American all-purpose flour is used, which gives the finished, cooked noodles a tender, yet springy texture. This is similar to the texture of either fresh or dried Chinese noodles.

How to Boil Chinese Noodles Successfully

Boiling can be the primary cooking process for Chinese noodles, resulting in an end product: cold noodles for a chilled appetizer or salad, or hot noodles for a soup. Or, it can be a method of pre-cooking noodles in order that they may then be used to make noodle pancakes or stir fried noodles such as lo mein or chow mein. At any rate, in any given Chinese noodle recipe, the first step is often to boil the noodles so that the recipe can commence.

Because Chinese wheat noodles are made from softer wheat, they do not cook the same way that dried Italian pastas made from very hard wheat do. It is very easy to over-cook these noodles, and end up with a mushy, slimy mess if one follows the usual method we are all taught for Italian pasta of boiling continually in salted (and sometimes oiled) water.

Some cookbooks suggest bringing the water to a boil, then adding the noodles, which will stop the boil. Then, the cook is instructed to turn the heat down to a bare simmer, and cook the noodles gently, stirring all the while.

That works fine so long as one does not have an electric stove which does not respond instantly when the heat is turned down, or one is not cooking in a thick-walled pot that retains heat well. In either of these cases, the cook is left with water boiling anyway, and risks overcooking her noodles through no fault of her own, since she followed the directions to the letter.

This is a simpler method to cook tender Chinese noodles, whether they are dried or fresh. I learned it from a Chinese chef at the restaurant where I used to work, and then witnessed several Chinese friends cook their noodles the same way. All of them told me it was the way their grandmothers taught them.

You bring your water to a boil. It should be in a large pot with plenty of water and room for the noodles “to swim around” as a friend once told me. (This part is like cooking Italian pasta–you need lots of water to cook noodles, no matter where you are.)

You do not salt it, as there is salt already in the noodles. You do not add any oil, either, as it serves little purpose in keeping the noodles from sticking–that is what you have chopsticks for! (When I asked the Chinese chef if he ever oiled the water with sesame oil or the like to keep the noodles from sticking, he looked at me like I had lost my mind. “What, and waste expensive oil? Why do you think we have chopsticks?” he said, shaking his head as he stirred a pot of noodles with a pair of long, cooking chopsticks.)

If you are cooking fresh noodles, take them from their package, and loosen them up, spreading them out on a clean plate. Fluff them up so they are not all stuck together–if you just dump the coiled contents of the pack into the water as is, you will end up with an unruly glob of sticky dough instead of noodles happily cooked into springy separate strands.

If you are cooking dried noodles, remove from the package the amount of noodle nests or straight noodles you are planning on cooking. (Check the package to see how long they suggest cooking the noodles in any case–even if they instruct you just to boil them, they will give you an estimated length of time. Notice that it is no longer than five minutes, which is much less time than it takes to cook Italian pasta.)

Do not overcrowd the pot! It is better to cook in several batches than it is to add too many noodles to the pot at once! I usually use seven quarts of water for a half pound to a pound of noodles.

Have ready beside the cooking pot, a pitcher or measuring cup of cold water. A colander should be in the sink, and if you are cooking several batches of noodles, you will need a mesh skimmer to remove the noodles from the boiling pot without pouring out the water.

When the water comes to a boil, put in your noodles. For dried noodles, just drop them in. For fresh, in order to keep them from wanting to clump together, lift them with both hands and sprinkle them over the surface of the water, scattering them over the pot.

As soon as the noodles go into the pot, your water should stop boiling, because the cool noodles have brought the temperature of the water down. This is good. While you are waiting for the water to come back to the boil, stir the noodles with a wooden spoon or better, a pair of chopsticks. Dried noodles that are coiled into nests need to be unwound so they will not stick together, and fresh noodles need to be separated as well.

While you are waiting for the water to come back to the boil, watch the clock. When it boils, pour a half cup to a cup of cold water into the pot to stop the boil. It should go down to a bare simmer. Stir the noodles again. Depending upon the thickness of the noodles, they may be done now–very fine noodles cook in about one to two minutes. If they are done, either remove them with a skimmer to a colander to drain in the sink, or pour them into a colander. If they are not done, repeat this process as necessary until they are done.

I use the chopsticks to pull out a noodle or two to test as I cook.

When they are finally done, remove them from the heat, pour the contents of the pot into the colander and begin rinsing them in cold water. This step is of paramount importance; rinsing in cold water removes any residual dissolved starch from the outside of the noodles, which keeps them from sticking together, and it helps firm the noodles up slightly, giving them a springy, bouncy quality under the teeth. I learned this from the old Chinese chef, and have since found it mentioned in a couple of out of print Chinese cookbooks from decades ago, but few modern cookbooks mention it.

If you are serving them cold, rinse them completely, using the water to chill the noodles thoroughly, while your clean fingers massage and detangle the noodles. If you are serving them hot, and are not going to cook them further (by stir frying, pan-frying or adding them to soup), then rinse them briefly in cold water, then switch to hot water, and then shake them in the colander to dry them. Rub a bit of sesame oil in them to keep them from sticking together, then put them back in the cooking pot to keep warm until they are ready to be served.

If they are going to be cooked further, go ahead and rinse them thoroughly in cold water. Then, you can hold them until you need them by keeping them submerged in cold water, which continues the firming up process. Many noodle shops precook noodles, then keep them soaking in cold water until they are served. Then, they are drained, scooped into warmed bowls, and topped with boiling soup which instantly warms the noodles to serving temperature. Noodles to be served cold also can be treated in this way: you can soak the noodles while you ready the sauce or dressing they will be served with.

Before tossing with the dressing, sauce, be certain to drain the noodles well so that the sauce is not unduly diluted by excess water. I sometimes use paper towels to blot the water off as well as shaking and tossing them in a colander.

That is it–my method for boiling Chinese plain or egg noodles in order to achieve the best texture and flavor. It sounds difficult and time consuming, but that is only because I explained it so thoroughly. It is really simple, and takes only about five to ten minutes from when the noodles go into the pot and when they emerge from their cold shower, ready to be cooked further or dressed up as I see fit. Noodles cooked this way are good to the last drop, or rather, string–as Kat illustrates here.

Tomorrow, look for a recipe featuring cold boiled noodles dressed in a delicious spicy sauce that makes a perfect light supper for a sweltering August evening.

Until then, here is a list of recipes I have already presented which use Chinese wheat noodles.

Za Jiang Mein: Wheat noodles with a meat and tofu sauce from Beijing–a great comfort food.

King Du Noodles: A variant of za Jiang Mein, which is sweeter and spicier, with black mushrooms.

Char Siu Lo Mein: Stir-fried fresh noodles with home-made roast pork, mushrooms, and greens.

Chicken Lo Mein: Once again, with greens and mushrooms. I love mushrooms.

Hunan Cold Spicy Noodles: They’re cold, they’re hot, their cold….whatever they are, they’re good.

20 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

The only think that would make this informative post better is another photo of your darling daughter, slurping up the noodle goodness. I’m glad for the advice on the difference between Chinese and Italian noodles because I’ve ..er…overboiled the Chinese ones on the extremely rare occasion and come up with the slimy mess. Not that I do that often, you understand……ahem.

Glad again to see you posting and recovering from the week from hell.

Comment by Nancy — August 13, 2007 #

Your wish is my command, Nancy–see Kat’s face after she has finished a second bowl of noodles.

Comment by Barbara — August 13, 2007 #

[…] continue article at Barbara delivered by conSALSITA […]

Pingback by Chinese Wheat Noodles 101 — August 13, 2007 #

Nice article!

Would homemade egg noodles made with all-purpose flour on an italian pasta rolling machine work well as substitutes?

I prefer homemade because I like to know where the eggs and flour came from, if you know what I mean.

Comment by Adam Ziegler — August 13, 2007 #

Adam–you are absolutely right. Fresh soft wheat flour pasta made in a pasta machine are perfectly good substitutes for Chinese noodles.

In fact, I am going to be posting about making fresh Chinese noodles in the near future, so stay tuned!

Comment by Barbara — August 13, 2007 #

My first pack of noodles from Chinatown had the wonderful instructions to ‘bathe the noodles in a large bath of water’ once they had finished cooking. I always have 🙂

Thanks for the noodle info – I’m just getting back into noodles in a big way so this is very timely!

Comment by Steph in the UK — August 14, 2007 #

Barbara, this is a fantastic post! Thank you very much! I adore Chinese food, and I love learning more about it from your blog!

Hey, why don’t you try and publish a cookbook with this material? 🙂

Comment by Maninas — August 14, 2007 #

Lots of good tips here! I knew to add cold water to stop the boil when making jiaozi, but didn’t know it applied to noodles as well.

Comment by Kitt — August 15, 2007 #

Yum.

I just got a hand-me-down pasta machine (one of those, “we never use this, you’re a foodie, you want it?” things), and would love to know how to make Chinese-style noodles with it. I’m having lots of fun playing with this thing. Reminds me of Play Doh when I was a kid.

Comment by Neohippie — August 15, 2007 #

Thank you for an informative and enjoyable post, Barbara!

All of these noodles are made of refined flour, right? Have you come across any whole wheat Chinese noodles, I wonder? I don’t think refined flour is poison or anything (eaten in moderation, as part of a meal), but if there is a whole grain option available, I would love to try it.

Comment by Nupur — August 16, 2007 #

Maninas–I have been thinking of doing just that–thank you for the vote of confidence!

Kitt–yep–it works for any wheat based boiled product. I do it with gnocci, too.

Nupur–as far as I know, there are not Chinese style whole wheat noodles. Let me see if I can find any, and let you know. But, generally, they are made with white flour.

Comment by Barbara — August 16, 2007 #

Any suggestions on a wheat noodle substitute for gluten free cooks? I’ve been using rice noodles and bean threads in some of my recipes, and I use brown rice pasta for American/Italian recipes. I’m not sure if any of these would be an appropriate substitution for wheat noodles though.

Thanks!

Mary Frances

Comment by Mary Frances — August 18, 2007 #

Mary Frances–you can use rice or bean thread noodles in the place of Chinese wheat noodles in many Chinese recipes.

The cold noodle recipes, especially, could be made with either cooked rice or bean thread noodles.

Comment by Barbara — August 18, 2007 #

Thank you Barbara, you solved a mystery for me. I recently was trying to recreate a Malaysian curry soup called Laksa that my boyfriend used to eat when he lived in Melbourne Australia. According to him I did a pretty good job, but my thin rice noodles ended up being way overcooked and mushy.

I am going to be making this soup again for some guests this week and I think I will try your methods this time. I think the idea of putting the cold noodles in bowls and pouring the hot soup over them is marvelous.

Cheers,

Benjamin

Comment by Benjamin — August 19, 2007 #

I’m sure it would be great! Your writing style, as well as your delicious recipes, are the very reason why I subscribe to your blog! 🙂

Comment by Maninas — August 21, 2007 #

Thank you, Maninas!

Benjamin–rice noodles are a little different. For them, you soak them before you use them, and barely boil them before you put them in the soup. You also rinse them in cold water, to carry any extra starch off of them to keep them from getting sticky.

But I am getting ahead of myself–rice noodles are a whole separate post, which is coming soon–I promise!

Comment by Barbara — August 23, 2007 #

Thank you, thank you! I am Chinese and lament that I don’t know how to cook my favorite comfort foods because I can’t read Chinese cookbooks. I’ve saved the pan-fried noodle pancake and za jiang mein recipe.

Comment by Jessica "Su Good Sweets" — October 10, 2007 #

what can i do to fix a big mistake? ive undercooked some bean thread noodles accidently thrown them in the carrot salad which haseverything except the dressing on it. will dressing soften the noodles overnight?

Comment by helen — April 26, 2008 #

[…] cook the noodles. The best primer I’ve found on dealing with egg noodles is over here; I never could follow the instructions, though. Mine always get tangled. So my standard strategy […]

Pingback by Aliette de Bodard » Blog Archive » Stir-fried beef with onions — March 18, 2011 #

[…] 5. Enquanto a cebola e o pimento cozinham em lume brando cozer os noodles. Colocar água ao lume num tacho grande, quando esta levantar fervura colocar os noodles e mexer com uma colher ou garfo para ficaram bem separados. O normal é cozinhar entre 3 e 5 minutos no máximo. Se cozinharem durante demasiado tempo ficam uma espécie de gosma! Os que eu comprei precisarem exactamente de 3 minutos. Encontrei informação sobre isso aqui, se quiserem ler mais, em ‘How to Boil Chinese Noodles Successfully’. […]

Pingback by Noodles com alheira e grelos | Coisas Boas — March 30, 2011 #