The Chinese Cookbook Project II: This Little Book

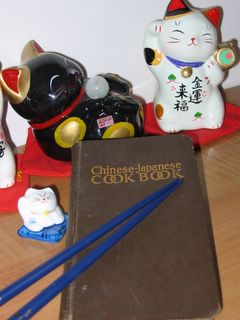

Surrounded by maneki neko, and shown with a pair of chopsticks in order to give a sense of scale, is Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna’s Chinese-Japanese Cookbook.

Earlier in this blog, I wrote about how I acquired a copy of Chinese-Japanese Cookbook by Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna, published by Rand McNally in 1914. What I did not talk about was the book itself, its provenance, and its authors. It turns out that while this may not be the very first Chinese cookbook printed in English, it yet is a fascinating piece of Asian-American history, the depth of which can only be guessed by looking at its rather unassuming exterior.

Reading the text itself is interesting; while there are many recipes that will sound familiar to students of Chinese cuisine, the way in which cookery itself is approached is very different than what we are accustomed to reading in cookbooks today. For one thing, the standard recipe format which includes a separate list of ingredients is present, but instead of putting the list in a column, it is written in paragraph style; this is fairly typical for cookbooks of this time period. More interestingly, the reader is advised on page 9 under the “Rules for Cooking,” that in order to make a rich stock for soup, “use only a quart of water for every pound of veal, mutton or beef bones.”

Especially considering that the recipes recorded in this book are supposedly handed down from Vo Ling, who was the principal cook to “Gow Gai, one time highest mandarin in Shanghai, (page5)” the passage regarding the use of veal, mutton and beef bones struck me as incredibly odd. As I have come to understand it, most Chinese stock recipes for soup rely almost exclusively upon chicken carcasses and pig bones.

Beef was seldom used in China for eating as oxen were necessary as beasts of burden. I have not run across any recipes for veal that I can recall, and my study has led me to believe that mutton and lamb are meats seldom eaten among the Chinese, except in the northern regions where the Mongolian influence is strong, and among Chinese Muslims. My personal experience has also born these findings out; with few exceptions, most of the non-American born Chinese people I have known have shown little liking for either lamb or mutton. One friend in culinary school who was from Singapore even wrinkled his nose and shook his head when offered a bite of rare lamb chop, declaring it to be “stinky meat.”

Other oddities that stood out as I read along was the recipe for fried bean sprouts (page 57) that directs the reader to fry one pound of bean sprouts in one quarter pound of fresh pork fat uncovered for five minutes, and then to add three tablespoons of soy sauce (which is called syou, apparently from the Japanese term, shoyu), and salt and pepper. So far, other than the large amount of pork fat, this sounds like a pretty standard and tasty bean sprout stir fry, however, after the addition of soy sauce, salt and pepper, the cook is told to cover tightly and allow it to simmer for fifteen minutes.

After fifteen minutes of simmering, the likelihood is that the bean sprouts are going to be on the slimy and mushy side, such that I cannot imagine any of my Chinese friends and aquaintances wanting to eat them. After directing the reader on how to grow ones own beans sprouts so as to avoid the canned lesser product, why then cook them until they have the same texture as the ones from a can?

Interestingly, recipes are presented for chow mein that include deep fried noodles, and chop suey; both dishes are Chinese-American adaptations or inventions, created to use available ingredients or appeal to American tastes. These recipes are recognizable even today, ninety-one years later, as dishes that you could walk into many American Chinese restaurants and order.

According to the preface of the book, by 1914, Chinese restaurants had spread out from the Chinatowns in large cities and had become competitive with even fine dining establishments. The book appears to have been written with the American housewife in mind; and instructions are given to help her recreate dishes she may or may not have tasted in a restaurant.

Fresh and canned bean sprouts are mentioned in the text, as is soy sauce and fresh water chestnuts. A recipe for bird’s nest soup is presented, which tells us that dried bird’s nest was also available, at least in Chinatown shops; these mentions give us a glimpse of what Chinese ingredients had begun to be imported into the American marketplace at the turn of the century.

The cooking fats mentioned most often are pork fat, lard, suet, chicken fat, and strangely enough, olive oil. The use of animal fat is not surprising; many older Chinese cookbooks and cooks I have spoken with have shown preference for the use of rendered animal fat in cookery, both for reasons of flavor and frugality. I suspect that the presence of olive oil reflects an adaptation to the most readily available vegetable cooking oil in the American markets at the time.

Just as interesting as the text of the book is the identity and history of its authors, neither of whom was Japanese, nor had ever been to Japan. Onoto Watanna was the pseudonym of Winnifred Eaton, and Sara (Eaton) Bosse was her sister. The two of them were the daughters of an Englishman, Edward Eaton and a Chinese woman, Grace “Lotus Blossom” Trefusis. Their father had been a silk merchant, and had met their mother, who had been adopted by English missionaries and educated in England, while he was visiting her home city of Shanghai.

The two had wed and gone to live in England for a time, then moved to Montreal, Canada, where Winnifred was born. Winnifred was a talented writer and at the age of fourteen, had articles published in a Montreal newspaper. She began selling stories to magazines in both Canada and the United States. At the age of seventeen, she moved to Jamaica to work as a stenographer for a Canadian newspaper. A year later, she moved to Chicago and began publishing short stories under the Japanese pseudonym, “Onoto Watanna.”

In 1899, she published her first novel, Mrs. Nume of Japan and two years later, after she moved to New York City, she published her second novel, which became a runaway success, A Japanese Nightingale. She is often credited as the first Asian-American novelist published in the United States.

Onoto Watanna ceased to be a nom de plume, and became a persona as Winnifred posed for publicity photographs dressed in kimono, and passed herself off as a Japanese noblewoman. She would not acknowledge her Chinese heritage because of the very strong racist attitudes and laws against Chinese immigrants in the United States at that time. American attitudes towards the Japanese were much more favorable (probably because of the Meiji government’s partnership with the American government and corporate interests in efforts to modernize Japan), and there was a great deal of interest in the “exotic” nature of Japanese society.

A topic that seemed central to many of Eaton’s works was that of romance between Anglo-American men and Japanese women. Considering her background, this is not surprising, however, it is interesting to note that she both plays into and subverts racial stereotypes about Asians in her works. (An older sister, Edith Maude Eaton, was also an author; she confronted racism against the Asians more directly by writing very gritty stories revolving around the plight of Chinese immigrants in North America under the Chinese pseudonym of Siu Sin Far.)

Sara Eaton Bosse did not seem to be a writer; no other works are attributed to her. According to Winnifred Eaton’s biographer and granddaughter, Diane Birchall, it is likely that Sara was attributed as a co-author in order to justify the addition of Chinese recipes. Of course, being Japanese, there would be no logical reason for Onoto Watanna to know how to cook Chinese food. Birchall also notes that while the sisters claim that the Chinese recipes were passed down from Vo Ling, she believes that it is likely that the cook was as fictitious a personage as Onoto Watanna. She further states that Winnifred Eaton was a terrible cook and boiled everything to death.

These facts could very likely account for the mushy bean sprout recipe and the out-of-place instruction to use veal, mutton and beef bones to make stock for Chinese soups. It is also possible that their mother, in cooking for their father, used such ingredients in order to create dishes that satisfied both to her husband’s English palate and her Chinese aesthetic sensibilities.

I am still doing research on this little book; considering it is a slender volume only one hundred and twenty pages long, there are plenty of interesting details and tidbits that hint at the history of Chinese cooking in North America. Even more fascinating are the details of Asian-American life at the turn of the century and the complex issues of race, gender and stereotypes that the works of the Eaton sisters record and explicate.

Stay posted; as I do more research, and actually read the fiction of Winnifred and Edith Eaton, I will likely record my thoughts here.

3 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

What a fascinating story! I’m looking forward to hearing more.

Comment by Christina — January 31, 2005 #

Hi, what a great blog with really interesting reading! I’m so glad that you left a comment so that I could find you, I will definitely come here often.

Have a nice day and pat all your 7 cats from me 🙂

Kind regards,

Dagmar

Comment by kissekatten — January 31, 2005 #

Hello, Christina–I will probably wait until after we move house to do more research on the Eaton sisters; we will be moving to a University town so I might be able to borrow copies of their biographies as well as some of their writings through the library there. Or at least sit in the library and read them and take notes. I am glad I read fast!

Dagmar–Glad to see you stopped by. I will definately give the cats your love.

Comment by Barbara Fisher — January 31, 2005 #