The Chinese Cookbook Project III: With an Open Mind and an Open Mouth

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese by Buwei Yang Chao

One book that is mentioned as being a seminal Chinese cookbook written in English is Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese, first published in 1945. This is with good reason; it is often cited as the first attempt to present to an American audience authentic Chinese recipes without resorting to fifteen variations upon chop suey, chow mein and egg fu yung, all Americanized standards popular in the Chinese restaurants of the day, and calling them “Chinese.”

As the book went through at least three editions, two of them revised and updated, and countless printings, I feel safe saying that it was successful at introducing American cooks to many of the core concepts, cooking techniques, ingredients and eating traditions of the Chinese kitchen.

How the book came about it an interesting one; the putative author was neither a writer, nor a lifelong cook, but instead, was a medical doctor. Ms. Chao relates how she did not learn to cook in childhood, but rather, while she was attending medical school at the Tokyo Women’s Medical College. While there, she writes in her author’s note to the first edition, “I found Japanese food so uneatable that I had to cook my own meals. I had always looked down upon food and things, but I hated to look down upon a Japanese dinner under my nose. So, by the time I became a doctor, I also became something of a cook. On my return to China, I surprised my old friends and relatives when I prepared a complete dinner of sixteen dishes the celebrate the opening of my hospital….How did I learn to cook so many things? My answer is: with an open mind and an open mouth. I grew up with the idea that nice ladies should not be in the kitchen, but as I told you, necessity opened my mind first. ” (xx Chao.)*

Dr. Chao, in her own self-deprecating way, sets the tone for her entire work; her main theme, which she reiterates over and over, is that -anyone-, with the application of an open mind, an open mouth, and the will to work hard and refine one’s ability to discern flavors and study, can learn to cook good Chinese food. By using herself as an example, a busy medical student, she assures her readers that they, too, can learn a subject which had previously been presented as very exotic and inscrutable, with mysteries that were too tangled for a mere Westerner to unravel.

Dr. Chao throws all of those ideals of the mysteriousness out of the window and applies her scientifically-oriented mind to the business of unraveling the knotted skein of philosophy, technique and ingredients that weave into the thorny problem of recreating Chinese foods in the setting of an American kitchen. She states that “The Chinese cook or housewife never measures space, time or matter. Hse* just pours in a splash of sauce, sprinkles a pinch of salt, does a moment of stirring and hse tastes the frying-hot juice out of the edge of a ladle, perhaps adds a little amendment, and the dish comes out right. It was only when I started on this cookbook that I began to get some measuring things so I can show you how to do it my way. What my way was, I could not tell myself until I measured myself doing it. ” (31-32, Chao)

Encouraging her readers to be fearless in experimentation, Dr. Chao suggests that most conventions of cooking, serving and eating to be “a little silly,” an understanding to which she came while learning Chinese cookery on her own in Japan. She suggests that it is very well and good and know how cookery is engaged in China, but that nothing replaces “a little thinking.”

“If you cannot get beef,” she writes, “get pork. If you cannot find an egg beater, use your head.” (xx Chao)

The writing style throughout the book is by turns opinionated and droll, with interesting choices in phraseology. One gets a strong feel not only for Dr. Chao’s personality, which is one of sharp wit and quick-thought, but also for the personalities of her husband, Professor Yuen Ren Chao, and their daughter Rulan. It is quite possible, considering Dr. Chao’s lack of skills in speaking or writing English, that not only did her daughter assist in writing the book, as proclaimed in the author’s note to the first edition, but that she and her linguist father, largely wrote the entire manuscript, with Dr. Chao providing the recipes, and technical information on cookery, ingredients and table manners.

Jason Epstein, in an article entitled, “Chinese Characters” written for the June 13, 2004 edition of the New York Times, contends that Professor Chao, whom he describes as whimsical and affable, wrote the text of the book, noting the use of the term, “eatable”, from the Old English root “etan,” instead of the more commonly used, but pretentious “edible, ” from the Latin “edibilis.” As Professor Chao was a celebrated linguist, it is entirely likely that he wrote the manuscript, but to not recognize the collaborative nature of the enterprise does a disservice to all involved. Epstein himself was the editor involved in bringing out the third revised edition from Random House books in 1967, and his description of the two authors is quite evocative, however, his characterization of the author’s note to the original edition as brutally insulting shows a great misunderstanding of how Chinese people tease each other affectionately in the guise of insults.

Having experienced this sort of teasing myself, I found reading the introduction as an intimate look into the family dynamics between Dr. Chao, her husband and daughter, and saw it as being full of passionate discussion, agreement, disagreement, laughter and filial love.

Probably the greatest linguistic addition to the Western lexicon of words pertaining to Chinese food came from the Chao’s book; Buwei Yang Chao is generally credited with the creation of the term, “stir-frying” to describe the action of “ch’ao.” Here Professor Chao’s influence as a linguist is crystal clear; the author(s) write “…the Chinese term, ch’ao, with its aspiration, low-rising tone and all, cannot be accurately translated into English. Roughly speaking, ch’ao may be defined as a big-fire-shallow-fat-continually-stirring-quick-frying of cut up material with wet seasoning. We shall call it ‘stir-fry’ or ‘stir’ for short.” (43 Chao)

I don’t believe I need to belabor the impact of the creation of a unique term in English to describe the specific cooking technique of ch’ao. Before the creation of “stir-fry” as a word meant to convey ch’ao, “fry” or “frying” was used, but the connotation of that word in English was woefully lacking in describing the full action that is ch’ao. Frying in European and American kitchens is a much more sedentary action, even the French term, “saute” is inadequate to describe what happens in stir fry cooking.

Since the word, “stir-fry” entered the English language in 1945, is has become part of common culinary parlance and in fact, is recognized even among people who have never eaten Chinese food in their lives.

It is odd to think that in writing a cookbook, the author(s) changed the English language along the way, for the better.

A great deal of useful, interesting and accurate information is also given on Chinese styles of eating, table manners and the standards of politeness which are in many ways, very different from what many Americans are used to. I was lucky to pick much of this up by watching it in action, but not everyone is observant in the same ways in which I am; the astute discussion of manners listed in the introduction is invaluable. The instruction of how to deal with bones, shrimp shells, chopsticks and wine drinking in the context of a family style Chinese meal or banquet are as applicable today as when they were written and the wry opinions presented still bring a smile and a chuckle to the reader.

The two chapters devoted to ingredients are divided into “eating materials” and “cooking materials.” Eating materials refer to fresh or preserved meats, seafoods, fowl, fish, eggs, vegetables, fruits, tofu, grains and nuts–things that make up the main ingredients for any given dish. Chao discusses how to choose the best eating ingredients and stresses the importance of fresh, clean food to successful Chinese cookery. Cooking materials present the varied condiments that are used to enhance or change the natural flavors of the eating materials in Chinese cookery. It is interesting to see how many of these items, such as fagara, or Sichuan peppercorn, oyster sauce, and fermented bean curd (called soy-bean cheese) are listed as being somewhat available in the US at that time.

Which brings us to the recipes.

There are no recipes for American style Chop Suey or Chow Mein to be found in this book, which is a great departure from cookbooks of the period.

What is found in flipping through the pages are recipes for an array of red-cooked dishes, steamed minced meat dishes, quite possibly the first recipes for dim sum (transliterated as tien hsien) specialties published in English, and vegetable dishes that utilize both Chinese and traditional American vegetables. There are a few recipes that are quite clearly adaptations of American ingredients into a Chinese culinary context–Salted Turkey is an adaptation of a traditional duck recipe to utilize the more commonly available turkey, and the Chinese Style Roast Chicken (there is a variant on Turkey as well) show a typical American cooking method fused with Chinese seasoning.

The recipes look delicious and many are similar to recipes I learned by watching Huy and the other chefs cook, especially when they were cooking for employee dinners. None of them look as if they were attempts to cater to American tastes–there are recipes for tripe, chicken gizzards and pig’s feet, though I would note that when this book was published, more Americans were apt to eat such “variety meats” as they were called at the time for a number of reasons. One, American households were not as generally affluent as they are now, and many lower-income people commonly ate lesser cuts of meat, including organ meats. This is not so true in these days of processed and convenience foods. And two, there was a war on, and meat rationing was in force, and variety meats were more available and less expensive than prime cuts. In fact, one of the selling points of the book was that it showed how to stretch smaller amounts of meat by cooking it with vegetables in such a flavorful way that no one would notice the lack.

Unlike the Watanna/Bosse book, I can see myself cooking from How to Cook and Eat in Chinese. In fact, I think that after we move and I become settled into my new kitchen, I will set forth to cook recipes from each of these out of print cookbooks, in order to evaluate the results. I think it would be a worthy project to engage in and record.

As I close the book and look at its plain yellow cloth cover, I cannot help but think that it is a shame that this little gem is out of print and thus is relatively unavailable to the student of Chinese cookery. The information presented therein, even though it was written more than fifty years ago, is still fresh, interesting, useful and relevant in today’s world. I only hope that by writing about it here, I can help rekindle interest in the book, and perhaps get it out to a wider audience while copies of it are still available in the used book market.

I know that there are plenty of people with open minds and mouths who would enjoy devouring the feast of cultural information, culinary experience, and linguistic expertise that are wrapped together with a liberal dose of sparkling humor in the pages of this book.

* The page designation xx is the actual Roman numeral used for the notes in the front of the book before the actual text of the book starts.

*“Hse” is the gender-neutral term for he/she coined by Professor Yuen Ren Chao, Dr. Chao’s husband, to make up for a third-person singular pronoun in English other than the rather formal and stiff sounding, “one.” As I will write later, it is quite possible that Professor Chao wrote more than a little of the manuscript of Dr. Chao’s book, since she admits in her forward that she “speak(s) little English and writes less.” (xx Chao)

12 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

Oh, wow. This is such a great post. I still can’t believe that books so influential to the way Americans view and cook ethnic foods can go out of print so easily. I’m curious – ingredients can be substituted a variety of ways, but what about equipment? I can’t imagine too many middle class American families buying woks today, but what about during the book’s era? Cast iron cookware perhaps? And what about steaming?

Awesome cats in the picture, by the way. 😉

Comment by Allen Wong — February 26, 2005 #

Great post, Barbara.

It’s always fascinating how things merge. I was aware of Yuen Ren Chao long before I was of his wife’s cookbook. There’s a Yuen Ren society named after him, dedicated to the study of Chinese linguistics in English. It was originally based at the University of Washington where he once taught. Here’s a link to the Yuen Ren Society:

http://www.geocities.com/yuenrensociety/

It’s also interesting to note that the eulogy you linked to (emanating from my alma mater, U.C. Berkeley) didn’t mention that he taught at the U. of Washington. A little Pac-10 rivalry?

Comment by Gary Soup — February 26, 2005 #

Thank you, Alan. I, too, am amazed and saddened that such an influential, and useful book is out of print. But the publishing industry is just that way; books go into and out of print quite quickly anymore, and there seems to be no rhyme or reason to it other than economics. You will find as I profile various books that there are a lot of really good books on the subject of Chinese cookery that are out of print and hard to find, which is part of why I am making this collection.

You are right–I should have mentioned the cooking utensils she suggests. For stir-frying, a thin bottomed skillet–she mentions nothing about cast iron, but that is what I would use, and she gives very complete directions on how to improvise a servicable steamer. Which is, in fact, how I used to improvise one until I got a set of bamboo ones.

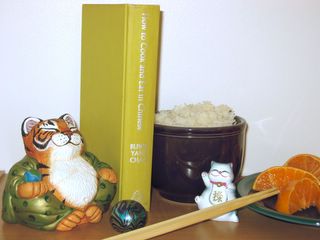

Glad you like the cats! I collect maneki neko and Buddha cats. The kitchen in our new house is going to be decorated with the maneki neko collection, and will eventually be redone in red, black and white.

Gary–I had found out about the Yuen Ren Society and I meant to post a link to it in the story–I should go back and edit it in. I will do that tomorrow. The two of them sound like they were wonderful people.

Their daughter teaches at Harvard, btw. A very scholarly family.

What I am finding is that many of these books have such interesting histories and stories to them. That is as interesting to me as reading the texts of the books themselves–the stories of the authors are turning out to be just as fascinating!

Comment by Barbara Fisher — February 26, 2005 #

<"I found Japanese food so uneatable that I had to cook my own meals. I had always looked down upon food and things, but I hated to look down upon a Japanese dinner under my nose. So, by the time I became a doctor, I also became something of a cook.">

Hahaha…I feel EXACTLY the same way now that I’ve been plunked into Japan. I don’t hate the food here nearly as much as some of the people I know, but it’s just not home! I’ve been learning quite a bit about just throwing things together for a meal…

Comment by etherbish — February 26, 2005 #

I thought of you, Ladi, when I read that passage, and smiled. I said, “I wonder how much Ladi is learning about cooking these days?”

It is like when we went out to eat with Morganna and her Uncle Wayne in Charleston–we went to a pan-Asian restaurant. It was good food, but you could tell that Japanese folks were in the kitchen. Zak ordered Ma Po Tofu and I ordered Sichuan dry fried beef, and while the dishes were tasty, they were obviously Japanese versions of Chinese dishes.

Nice, tasty, but not Chinese.

Comment by Barbara Fisher — February 27, 2005 #

I first learned of Dr. Chao’s wonderful cookbook when I was acquainted with her granddaughter in the early 1970s. This book had a major impact on the diet and nutrition of our whole family. Our copy of “How to Cook and Eat in Chinese,” which our friend Canta Bien so kindly gave us, was the first cookbook my new husband and I owned jointly. During our years as graduate students and young parents living on a tight budget, we turned again and again to the wisdom and humor of Dr. and Dr. Chao. We developed a lifelong enthusiasm for Chinese cuisine that has now persisted into the third generation. Our daughter and her Chinese American husband now use some of those same recipes, and I’m sure our little granddaughter will come to love them as our whole family still does. It was a pleasure to be reminded of this exceptional and influential book.

Comment by M.B. Adams — April 1, 2008 #

Name correction to above post: Canta Pian

Comment by M.B. Adams — April 2, 2008 #

I just bought a copy of this book at a library sale for $2.00. It is a 3rd edition revised in 1963 in brand new condition. I feel very lucky to have it being out of print. I love your site it is a great inspiration for all of us chinese chef’s on the rise.

Comment by Richard Parker — November 17, 2008 #

Newcastle Australia friends (he then Prof of Mathematics/she writer John & Zeny GILES introduced me to University of Washington Prof of Mathematics Isaac NAMIOKA and his writer wife Lensey – with whom ten years ago my wife and I stayed briefly in Seattle. Lensey is the 4th daughter of Yuen Ren CHAO and Buwei YANG (CHAO). Then I learnt about Lensey’s illustrious parents – about “stir-fry” – and about Isaac’s Japanese background – since I was then, up until May this year, resident in Japan (totally 16 years)! Now back in Australia. My tastes in food seem to be wider than some other writers to this page – any ethnic/regional/national cuisine goes down well in front of me – including Japanese (though maybe I was fortunate in those friends who introduced me to its fantastic range) of course! Thank-you for this site.

Comment by Jim KABLE — November 15, 2009 #

I have a yellowing paperback copy of the third edition of How to Cook and Eat in Chinese. Apart from what I learned from my mother and grandmother about cooking, that book and The James Beard Cookbook were what I used to learn how to cook.

At first, I thought of what I was doing as following the recipes. But I quickly learned that the real genius of the book is Dr. Chao’s explanations of the principles behind each class of dish, and her basic, practical attitude. It has served me well for many years.

Comment by John Tate — May 14, 2012 #

Some years ago I found a copy in wonderful condition in a bookstore for a dollar. It appears to be the first edition, but the publisher is unnamed, and the author’s name is on the spine, at the bottom, where one would expect the publisher’s name. There is no date. There is a foreword by Hu Shih, and Pearl S. Buck’s introduction. There is no copyright notice, and my guess is that it was privately printed by the Doctors Chao to provide gifts to friends. I had cooked for years from the second or third edition, which I loved, but this book I treasure. I wonder it anyone knows anything about its history.

Comment by Joel Shimberg — May 20, 2012 #

I found this article for searching for more information about this book. I have a copy and you would not believe how battered it is. It sounds like I’d better not wait around to replace my copy.

All this re-interest in this cookbook was triggered by Tyler Cowan’s “An Economist Gets Lunch”. He has a great article about shopping for a month in a Chinese grocery store. He also tells you how to find a grocery store like that and I used those instructions to find a great local Asian store. Now I have all this interesting stuff to cook! I think I am going to try and cook my way through this book. I’ve done red cooking before and it’s time to try it again.

Comment by Teri Pittman — June 14, 2012 #