The Chinese Cookbook Project V: America’s Dim Sum Pioneer

Henry Chan is a man with a vision.

Henry Chan is a man with a vision.

He envisioned a dim sum restaurant in the United States with impeccable service, a refined atmosphere and clean bathrooms.

And eventually, after a great deal of family drama between he and his father, he managed to turn Yank Sing, the restaurant his beloved mother, Alice Chan, started in 1958, into the restaurant he had seen in his dreams. Now, forty-seven years later, Yank Sing is known throughout the United States and the world as -the- place to go for dim sum in San Francisco, a city teeming with dim sum palaces and teahouse dives.

“Dim sum”, for those who are not familiar with the term, literally means, “touches the heart,” or “dot the heart.” It refers to a variety of small snacks which are eaten with tea in special restaurants called teahouses. The practice of going out for dim sum is known as “yum cha,” which means, “to drink tea,” and it is a weekend tradition in Hong Kong and the southern province of Guangdong in China. The tradition of teahouses spread wherever Cantonese people who left China settled, and it is said to have first appeared in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1940’s or 1950’s. Certainly at the time that Alice Chan and her son Henry, arrived in the early 1950’s with the rest of their family, she got a job at Lotus Garden, one of the two existing dim sum restaurants in San Francisco.

The secret to Yank Sing’s success is not only that Henry Chan held it to a higher standard than all the other dim sum restaurants in San Francisco, insisting that the service and dining room be as elegant as any fine dining establishment that American foodies love. The heart of Yank Sing lies in the beautifully prepared dim sum specialties from a menu which includes a staggering one hundred varieties. Though “only” about sixty varieties of dim sum are available on any given day, each type is created lovingly by hand and with exquisite care in huge kitchens where highly skilled workers wrap up to 360 potstickers an hour.

That is a lot of potstickers.

Dim sum is best experienced in a restaurant or teahouse setting, but I have been teaching home cooks how to make it for about seven years now, and my dim sum classes have been constently the most popular ones I have offered. I have been experimenting with home recipes for dim sum for longer than that, developing my own ways of making various teahouse favorites.

As an outsider to Chinese cookery, I am put at a unique vantage point when it comes to evaluating dim sum recipes–most Chinese or Chinese Americans have a plethora of kitchen tricks that they grew up with, shortcuts that have been passed down in their families for generations. Non-Chinese Americans such as myself did not grow up with hese kitchen traditions, so in a lot of ways, we are more able to see clearly whether or not a recipe is written in a truly user friendly way, and if the instructions will help the home cook create not only an edible result, but a flavorful one, too.

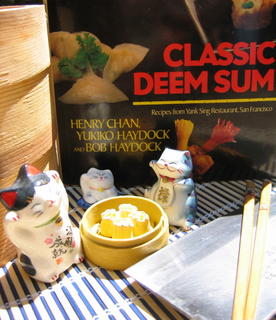

The recipes in Classic Deem Sum: Recipes from Yank Sing Restaurant, San Francisco, by Henry Chan, Yukiko Haydock and Bob Haydock (Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, New York, 1985) represent some of the clearest and most “authentic” dim sum recipes I have had the pleasure to work with and peruse.

When I say they are clear–they are written quite simply, with step-by-step instructions, in a format which is easily followed by novices and old hands at Chinese cookery. I attribute that to the work of Henry Chan’s co-authors, the Haydocks, who had previously produced three other cookbooks on Japanese cooking for American audiences.

Interestingly, this is the first book I have ever seen which advocates the use of a tortilla press in rolling out har gow or potsticker wrappers, a practice I had not heard of until it was suggested to me by someone out there in the blogosphere. Every other Chinese person I knew of who made wrappers from scratch for their own dim sum specialties (when they made them at all), rolled them out using a small rolling pin. However, not long after first hearing about the tortilla press, I went out to eat at Shangri la in Columbus, and lo and behold, the owner was sitting in a corner of the dining room, pressing har gow wrappers with a tortilla press and then wrapping them with nimble pinches of her fingers.

Since the dim sum at Shangri la is the best I have ever had in Ohio that I didn’t have diddly-squat to do with making, I couldn’t help but figure that the practice of using tortilla presses as a time-saving device in dim sum restaurants was not only widespread, but didn’t seem to hurt the flavor or texture of the dumplings in any appreciable fashion.

So, there you are, folks–cross-cultural grassroots cooking advice, brought to you by a friendly blogger with a penchant for out of print cookbooks. What more can you want from life?

The reason I use the loaded term “authentic” to describe the recipes (even though it is hardly “authentic” to use a tortilla press in a Chinese kitchen) is simple: the authors call for lard, pork fat and pork to be included in nearly every dish, a sure sign that a traditionalist is at the helm in the dim sum kitchen. Pork fat is the reason why so many dim sum specialties taste so blasted good and are so juicy. (That is also why the Chinese government recently condemned dim sum as not being a particularly healthy food, much to the outrage and dismay of teahouse fanatics throughout the country.) Pork and its derivatives are in almost every recipe in Classic Deem Sum, which means, if you are Muslim or you are cooking for an Islamic friend, I’d suggest you not make dim sum out of this book.

However, if there are no dietary prohibitions against the pig in your chosen religion or lifestyle, I cannot suggest more strongly that you look up this book on Bookfinder, and pick yourself up a copy. While it is sadly, and unjustly out of print, there are quite a few copies available, including first editions and copies signed by Henry Chan himself, if you are into collecting such things.

Until you can get your hands on a copy of the book, however, high thee hence to the nearest dim sum palace, pour yourself some tea and enjoy some dumplings and buns.

And remember–even though I disagree with Emeril Lagasse on many points, I concur with him on this point:

Pork fat rules.

6 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

Every chinese will agree with your statement about pork fat as that is what they can’t do without in their food. Some foods like dim sum, egg tarts just don’t seem right without lard.

In Malaysia, we get the ones without the pork fat where they will replace it with seafood like scallops and prawns. Does not taste that nice but it’s quite close to the real thing.

Comment by boo_licious — July 21, 2005 #

I am one of the few Americans I know who will not recoil from the thought of eating lard. I grew up with pastry made from home-rendered lard and bacon fat used to cook food in. I still save my bacon grease and will use it to cook with–sometimes in the wok.

If I am doing Chinese food, for example, I will pop a bit of bacon grease from the jar I save it in into the wok with the peanut oil, just to add a little bit of extra flavor. Not too much–American bacon is very smoky, and I don’t want that flavor to overpower the other flavors in the dish. I just want that extra little kiss of flavor.

Of course, when my Muslim friend is over–I don’t do that.

Comment by Barbara Fisher — July 21, 2005 #

For me it’s not the pork-fat componant (I’m in favor of porkishness, although I think lard has an unpleasant taste) but the difficulty of finding enough adventurous eaters to make the dim sum experience broad enough, ie to allow one to eat lots and lots of different things.

Although I cannot eat spicy-hot things nor reduced cooked tomatos(not a problem in Chinese food)I feel that if it’s on the dim sum cart, it’s edible. Palatable? That’s why you need several(or more) people, to share those less-than palatable tries and fight over the extra-palatable ones.

It’s also good to have enough people to supply lots of conversation–I think going to a dim sum restaurant is, in social terms, like eating fondue but much more fun!

Comment by wwjudith — July 21, 2005 #

Some lard does taste funny. Sometimes that is because it has started to turn rancid, sometimes, I think it has to do with the hog, or the way the lard is produced. My favorite pie crusts are made with 1/2 butter and 1/2 lard, though. It produces the flakiest, tastiest pastry.

Dim sum is all about social experiences surrounded by and lubricated with tea and excellent food. At least, that is so with me.

Comment by Barbara Fisher — July 22, 2005 #

Dim sum restaurants with clean bathrooms? And dim sum only on weekends? Blasphemy! 😉

What always amazes me with dim sum restaurants is the variety of food on order. The training of a competent dim sum chef has got to be something else entirely even though a lot of the dishes consist of variations on a very few basic themes. As a side note, because of those themes, it’s actually quite possible to get a full dim sum experience with a relatively small group if you can order your dishes instead of waiting for what comes around on the carts.

Comment by etherbish — July 23, 2005 #

Lo, the grandfatherly dim sum chef who used to work with Huy in the restaurant I worked, was amazing. We served no dim sum there–he was an underchef, but he would make dim sum for breakfast or lunch for the staff. His fingers would fly over the dough, and he would explain carefully to me what he was doing.

The first dim sum I ever tasted was his–he had made turnip cakes for breakfast and he and his working partner, Jin, were eating it in the kitchen. Of course, I wanted to know what it was, and they offered me some, and I loved it at first taste. Which thrilled Lo, because he expected me not to like it.

After that, he would make something new and interesting for lunch every shift I worked. Shrimp boats, har gow, potstickers, dumplings shaped like little rabbits, stuffed tofu, tofu skins, that sort of thing.

And I loved it all.

But he never explained to me about dim sum. Mei did–she said that what he did was specialized and he was spoiling us with all these dainty dishes for lunch. She explained that he had apprenticed something like eight years to learn how to make dim sum, in Hong Kong and Guangdong, and then he had worked all over China.

He was very old, but the kitchen was in him–he said he would stop making dim sum when he stopped breathing and not before. Kind of like the chef in “Eat Drink, Man, Woman.”

Comment by Barbara Fisher — July 23, 2005 #