The Locavore’s Bookshelf: Animal, Vegetable, Miracle

Barbara Kingsolver is one of my favorite writers.

Her prose is graceful, eloquent and spare; she is the master of poetic description punctuated with the occasional baldly-stated observation of ugly, yet undeniable truths.

With her training and background in evolutionary biology, Kingsolver cannot help but report on both the incredible beauty the natural world offers as well as the realities of life: blood, excrement and death. She does so in a prose style that is by turns lyrical and plainspoken; her voice is inextricably tied to the Appalachian farmlands of her Kentucky childhood and her current home in Virginia.

In her newest book, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, she brings her storytelling skills and incisive viewpoint to the chronicle of her family’s experience of spending a year (2005, to be precise) eating locally. What food they did not grow, preserve, process and butcher themselves, they bought from farmers within their home county, with the exception of flour, salt, coffee, cocoa and spices.

Far from being a narrative of deprivation, the book is a goldmine of gems gleaned from an authentic life well lived. Kingsolver is such a good writer, she can make even the most mundane and odd of topics, such as the mechanics of natural (meaning, unassisted by humankind) turkey reproduction a tale of hilarity worthy of a stand up comic. Her ruminations on the prolific nature of zucchini squash and an overabundance of tomatoes at the height of summer are also funny, while also being instructive. (Lesson: don’t plant so darned many summer squashes next time.)

But it isn’t all farming tales of adventures in animal husbandry and gardening woes; Kingsolver and her family also delve into the arts of cooking, food preservation and cheesemaking. Yes–cheesemaking.

Kingsolver herself allows as to how cheesemaking is generally considered beyond the pale for even the most “back to the land” foodies of the world, such that she notes, “If the delivery guy happens to come to the doore when I am cutting and draining curd, I feel like a Wiccan.” Meaning of course, she feels as if she is engaged in something esoteric, alchemical and somewhat, shall we say, eccentric.

Eccentric as cheesemaking and the daily baking of bread may be to most Americans, Kingsolver’s family, who also raised their own chickens for eggs and meat, and turkeys and made sausages from some of their birds, as well as growing and preserving all of their own fruits and vegetables, did quite well. Her narrative is punctuated by asides describing the ecological and health impacts of processed foodstuffs, industrial agriculture the cultural and political fallout of same and written by her biologist husband, Steven Hopp, which greatly enhance the month-by-month story Kingsolver weaves.

Camille Kingsolver, her elder daughter, also joins the writing team, outlining seasonal recipes for each chapter, using the bounty the land created at each step of the harvest, while also bringing her own unique vision to the year-long project.

While not as factually dense and argumentative as Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle deserves to be read just as much, if not more, because it takes Pollan’s ideas and extends them over an entire year of meals, not just four. Kingsolver also shows the effects of her family’s experiment not only on herself, but on each of her family members, as well as friends and community members, which, I believe makes for a more interesting and enlightening narrative. Through her eyes and prose, we can see how important it is for us to know where our food comes from and how it is produced, as well as how a mostly urban family -can- actually raise a significant portion of one’s own food, not only ethically and healthily, but inexpensively as well.

A good read, one that I cannot recommend highly enough.

Nina Planck Stirs the Pot; Vegans Get Steamed: Film At Eleven

You know, I used to like Nina Planck.

Now, I am not so sure.

I wrote a review of her book, Real Food, when it came out in hardcover last year, and although I noted it was not perfect, I mostly agreed with her premise and information. I did and still do have reservations about some of her facts, because some of them come from outdated sources, but in general, I agree that the best diets for humans include mostly unprocessed whole foods, with emphasis on fresh vegetables, grains, fruits, nuts with some pastured dairy, meat and wild-caught fish.

But, I have to say that her diatribe against vegan parenting from the May 21 edition of the New York Times Op Ed pages is not only mean-spirited and filled with scare-mongering opinions, she plain old gets many of her facts wrong. Prompted by the sentencing of two vegan parents in Atlanta for the murder of their six week old infant whom they fed on soymilk and apple juice, Planck goes on the warpath against vegan parents, using this case of obvious parental neglect and abuse as an excuse to vent her ex-vegan spleen against a group of people, who on the whole, do their best to feed their families ethically and well.

And as far as I am concerned, that is just uncalled-for, in large part, because the fact that these parents were vegans was not the issue. The fact was that they had no clue how to feed an infant was the issue, and they starved him to death. Even the prosecutor in the case said, “No matter how many times they want to say, ‘We’re vegans, we’re vegetarians,’ that’s not the issue in this case. The child died because he was not fed. Period.”

The prosecutor knew the truth, which is that no responsible vegan parent in the world would feed an infant, who was born three months premature, a diet of apple juice and soy milk. (Note–have you ever looked at a carton of soy milk? Somewhere on every carton of soy milk I have run across is a statement something like the following: “Not to be used as an infant food.” One cannot easily misunderstand that, unless of course, one is illiterate, stupid, or a murderer.)

The prosecutor got it, but Nina Planck did not, and she used this tragic case of parental ignorance, neglect and cruelty, to step up on her soapbox and paint all vegan parents as irresponsible kooks.

In her essay/article/screeching rant, entitled, “Death by Veganism,” she states in her final sentence, “Children fed only plants will not get the precious things they need to live and grow.”

She also said, “A vegan diet is equally dangerous for weaned babies and toddlers, who need plenty of protein and calcium. Too often, vegans turn to soy, which actually inhibits growth and reduces absorption of protein and minerals. That’s why health officials in Britain, Canada and other countries express caution about soy for babies. (Not here, though — perhaps because our farm policy is so soy-friendly.)”

Actually, let’s hear what the ADA, The American Dietetic Association, has to say about the suitability of a vegan diet, which can include soy formula for babies who are not breastfed, straight from their own website.

The ADA’s official position on vegetarianism reads thusly: “It is the position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada that appropriately planned vegetarian diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate and provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases.…This position paper reviews the current scientific data related to key nutrients for vegetarians, including protein, iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin D, riboflavin, vitamin B-12, vitamin A, n-3 fatty acids and iodine. A vegetarian, including vegan, diet can meet current recommendations for all of these nutrients. In some cases, use of fortified foods or supplements can be helpful in meeting recommendations for individual nutrients. Well-planned vegan and other types of vegetarian diets are appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including during pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood and adolescence.

Did you notice that the ADA website specifically mentions that the Dietitians of Canada concurred with their position? So, uh, which Canadian health officials are expressing caution against the use of soy in infant diets?

We’ll never know, because Planck doesn’t cite her sources.

And that, my friends, is why I am pretty well steamed, even if I am not a vegan.

I am steamed, and I stand with all those steamed vegan parents who are rightfully huffing about Planck’s opinion piece, because she is not only not a nutritionist or a pediatrician, she is stating her opinions as facts, and is not backing up her assertions.

She is not an authority on nutrition or health, so her argument, unless she appeals to a qualified authority, is unsupported.

When she does appeal to authority, such as the unnamed British and Canadian health officials, she does not cite her sources, so we can do some fact checking, in order to see if they really said what she says they said.

If you go to her website, Planck does tell us that talked with “many sources” in order to write her op-ed piece.

But she gives us no names; instead, she says, “Some readers asked about my sources. Among many sources for this piece, I interviewed a family practitioner who treats many vegetarian and vegan families. The doctor’s comments were useful but too long for the Times. Here they are:

‘The most significant issue with vegan infants is growth. I have seen cases of severe anemia and protein deficiency in vegan infants resulting in hospitalization and blood transfusion. Most breast-fed vegan children will do okay until solids are introduced, as long as the vegan mother is well nourished. Most commonly you see Vitamin B12 and iron deficiencies in vegan children. Vegan families must place close attention to protein sources, calcium, Vitamins D and B12, and iron. Often this can be achieved via fortified foods, but I’ve seen that not all vegan parents want to choose these types of foods. Most vegan families I’ve met don’t understand the importance of fat intake in the cognitive development of the baby.’ The doctor also reiterated what informed parents know: that soy milk is ‘completely inadequate’ for babies.”

This unnamed physician could be a great source of information; he could have done research that has been written up in a peer-reviewed journal that supports Planck’s assertions. However, we have no way of knowing that, because he is not named. We cannot look him up and see if he really is on the up and up, or is just some quack whom Planck happens to know.

In fact, we don’t know how many of her “many sources” she talks about are really qualified authorities.

In fact, we don’t even know if they are real or not; we just have to take her word for it.

I’m sorry, but since she has made one blatantly fallacious statement, which is the crux of her argument, that being that a vegan diet is completely inadequate to feed infants, I am not going to just give her the benefit of the doubt on the existence of her sources.

I mean, if a writer is going to go against the ADA’s official stance, it behooves her to get her facts straight on the issue she is on her soapbox about.

The fact is, Planck is full of it on this issue. She is making it sound like -all- vegan parents are as misinformed, incompetent, negligent and cruel as the parents of Crown Shakur, the baby who starved to death in Atlanta. She is making it sound like all vegan parents are feeding their babies soy milk from cartons which specifically state that it is not a proper infant food. She is making it sound like all vegan parents are criminally negligent, just like the two who have been sentenced to life imprisonment for murder, when the truth is, most vegan parents go out of their way to feed their infant children the best food in the world for them: breastmilk.

What does the first sentence on the Vegan Society’s webpage on infant feeding say?

“Breast is best.”

Not, “Apple juice and soy milk is the way to go.”

Apple juice and soy milk don’t even make it to the second sentence, or the third, fourth of fifth. The next best choice cited by the Vegan Society is soy-based infant formula, which is also deemed an acceptable second-best to breastfeeding by none other than the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The fact is this: no responsible parent, vegan or omnivore, would feed their infant child a diet consisting of apple juice and soy milk. Such a diet is not recognized by anyone as adequate or preferable, so why is Planck trying to scare the New York Times readers into thinking that vegan parents are a bunch of irresponsible dimwits who don’t know how to feed their kids?

Well, I hate to say it, but she probably did it to sell more copies of her book, which is coming out in paperback next month.

Okay, maybe I am being too cynical.

Maybe Planck really believes that there are a bunch of vegan parents out there starving their kids to death and she wants to warn everyone to be on the lookout for babies being fed on diets of soy milk and apple juice. Maybe she thinks she is doing some good by giving the people who may never have met a vegan in their lives the idea that they are all baby-killers. Maybe she thinks some vegan parents will read her work and see the light and stop eating such a kooky, faddish diet.

Or, maybe, she is just a bit of a kook herself.

I think I will go back to my first, albeit cynical, thought because I don’t like to think that she is a kook or a vegan-hating bigot.

Planck is just out to sell some books by engaging in a provocative bit of yellow-journalism by slinging some mud at an easy target.

The problem is–at least in my eyes–is she aimed mud at the vegans, but splattered herself thoroughly in her own muck by not citing sources for her “facts” and for stating easily discovered fallacies as truths.

I hate to say it, but I don’t think that I will be reading her next book, Baby Food, which she is researching now, on the subject of real food for babies, a subject which all of my readers -know- I am interested in.

I’d love to read it, but I just don’t think I could stomach it.

Chocolate Raspberry Cheesecake For Dan’s Birthday

My dear friend and brother, Dan Trout loves cheesecake. Dan loves it so much, he has been known to eat entire cheesecakes in a sitting. After the New Years Eve debut of my Pomegranate Cheesecake, he was heard to boast that he could even eat one of my cheesecakes by himself.

Well, as a cook and a big sister, I felt that gauntlet fall, and I picked it up and the challenge was made. I wanted to see if I could make a cheesecake which would defeat Dan’s immense gluttony for the creamy, cheesey, sweet and glorious confection.

By the way, I wanted to point out that Dan is not my birth brother, but he looks enough like Zak and I that people are continually asking if we are related. Dan’s wife Heather also looks enough like us that folks seem to think we are all siblings or cousins or something. I find this amusing, considering I grew up in West Virginia. Think about it.

At any rate, he and Heather are part of my family of choice, which is equal in importance to me as my blood family. Besides, in a metaphysical sense, we are all related, one to the other, in the great web of life–humans, animals, plants–everything that exists–is part of the same singular being.

So, yeah, Dan is my brother, and that is how it is, and it is all good. (Yes, Heather that makes you my sister, which makes your husband Dan your brother, too–see what I mean about growing up in West Virginia and how amusing–and confusing–all of this metaphysical stuff is? I feel like I should make up a metaphysical soap opera called “All My Relations.” Though, if I am making it up, maybe it should be a soup opera, not a soap opera. But, I digress.)

What was I talking about? Oh, yeah, cheesecake! (Sleep deprivation does interesting things to my mind.)

Anyway, I asked Dan what kind of cheesecake he was wanting for his birthday, and he said, “something chocolate.”

Something chocolate it was.

I decided to make a chocolate cheesecake with a chocolate-almond crust (knowing as I did that Dan loved almonds) with a raspberry jam swirl in the batter. Then, I would paint the top of the cheesecake with raspberry jam, and decorate it with fresh raspberries and a sprinkling of sliced almonds.

I mean, I just couldn’t make a plain chocolate cheesecake, could I?

I also decided to flavor the batter with espresso. In order to extract the espresso and liquify it in a form that would not cause the melted chocolate to seize up, I melted a tablespoon of butter with a tablespoon of heavy cream, then stirred into this warm fat mixture instant espresso powder, a staple in my baking supply cabinet. Then, after the chocolate was melted, I stirred this into it and it punched up the chocolate flavor immensely.

For the chocolate, I used bittersweet Scharffen-Berger; it gave the right depth of flavor and color to the batter which ended up looking like chocolate nougat before it was baked and milk chocolate after it was baked. I highly suggest using a quality chocolate in this recipe, because you really want the flavor to shine; it has to hold up to the cheese and raspberry.

For the crust, I used Nabisco Famous Chocolate Wafer cookies, crushed into fine crumbs, along with almonds similarly treated, and butter. No sugar was necessary; I wanted the dark, somewhat bitter mocha-chocolate flavor of the black-colored cookies to shine through, with the almonds supplying a toothsome texture.

The jam that I used inside and on top of the cake is an organic seedless raspberry spread made in Italy called Fiordefrutta. It has an intense raspberry flavor with a delightful tartness that offsets the natural sweet flavor of raspberries. Too often raspberry-flavored baked goods are one-note affairs with sweetness being the order of the day. Not so with this product; it is a balanced flavor that smells sweetly of wildflowers and sunshine. (However, if you cannot get Fiordefrutta, any high quality seedless raspberry jam with a good balance of sweet and tart will do.)

What did Dan think of his birthday cake?

Well, it was like this: I gave him a huge slab of it, which he ate quite easily, to everyone’s amazement. Morganna couldn’t finish her piece (and she commented, “Mom–your cheesecake recipes are why German people are fat! Germans always want to overload their baked goods and go just one step farther and add just one more thing with fat in it to them!” I pointed out that I knew plenty of German chefs who were not only not fat but downright slender, but I still had to giggle, because if you look at the old photographs of our family’s German ancestors, they did tend toward the zaftig. As do I, for that matter.), so he offered to finish it for her.

He couldn’t do it. The last three bites were left untouched. (Correction: The last three bites were from Heather’s half a piece that Dan could not finish.He successfully finished Morganna’s cheesecake, as well as eating his own slab, as well as most of the rest of the piece Heather had. His capacity for gluttony in the face of cheesecake is still impressively undimmed. I did not mean to tarnish his reputation; I was merely mistaken.)

I sent the majority of it home with he and Heather, and I asked him to report on how long it lasts. I like gifts that keep on giving, and baked goods that are so good you just cannot sit down and polish them off in a day.

You have to parcel out the goodness and savor it for a while.

And when the goodness is creamy, mocha cheesecake with sparkling raspberry fruit essence swirled through it topped with almonds and fresh raspberries–it is an indulgence worth savoring. I mean, if you are going to take the caloric hit of a cheesecake, make the experience worth every blessed calorie that slides over your tongue.

Chocolate Raspberry Cheesecake

Ingredients:

1 package Nabisco Famous Chocolate Wafers

1/4 cup sliced almonds

8 tablespoons butter, melted

3 pounds cream cheese, softened

1 1/2 cups sugar

3 teaspoons vanilla bean paste

3 large eggs

3 large egg yolks

3 squares Sharffen-Berger bittersweet chocolate (about six ounces)

1 tablespoon butter

1 tablespoon heavy cream

1 tablespoon espresso powder

1/3 cup seedless raspberry jam, divided in halves

1/4 cup raspberry jam

fresh raspberries for garnish

sliced almonds for garnish

Method:

Preheat oven to 375 degrees F.

Using a food pocessor, grind up the cookies and almonds into fine crumbs. While the processor is running, drizzle in melted butter, and process until the mixture forms clumps like wet sand.

Remove from food processor and dump into the bottom of a locked ten-inch springform pan. Using clean hands, press the crumbs evenly into the bottom and partway up the sides of the pan, then bake in your preheated oven for fifteen minutes. (If you have a convection oven, bake for ten minutes.)

Remove from oven and cool completely. Turn oven down to 300 degrees, and put a baking pan full of water in the bottom of the oven, in order to create a steamy, moist baking environment.

Beat together the cheese, sugar and vanilla on high speed (a stand mixer with a large bowl makes this easy) until well blended, light and fluffy. Scrape down bowl and beater, and beat for another two minutes, just to make sure.

While the cheese and sugar are beating, melt the chocolate by whatever method you prefer. I chop it finely with a chef’s knife (some people grate it by hand or use a food processor to grate it, or they use one of these nifty chippers), and then melt it in a glass bowl in the microwave. I microwave it on high at ten second intervals, after the first interval being twenty-seconds, stirring after each melting. Keep this up until the chocolate is fully melted with no lumps.

Meanwhile, heat up the tablespoon and butter and cream in a microwave until the butter melts and the mixture is steaming hot. Mix in the espresso and stir until a thick, dark paste forms. Stir this into the chocolate.

Whisk together the eggs until they are well beaten and then add to the cheese mixture. Beat until well combined, scraping down the bowl at least once.

Once eggs are combined with the cheese batter, add the chocolate mixture, beating until well combined and scraping down the bowl at least once.

Pour one half of chocolate-cheese batter into prepared springform pan. Add 1/2 of the first portion of raspberry jam by small spoonsful dropped randomly into the batter in the pan. Swirl with a knife to distribute. Pour the rest of the chocolate cheese batter into the pan and repeat the process with the other half of the first portion of raspberry jam.

Place the cake in the oven, on the center rack and bake for one hour and fifteen minutes. (Bake for fifty minutes if you have a convection oven.)

The cake is done when a tester piercing the center comes out looking mostly dry, and the cake is a warm brown color and appears to be set. Cool the cake on a wire rack on the counter until it comes to room temperature.

When the cake is slightly warmer than room temperature, take the second measure (1/4 cup) of raspberry jam, and warm it slightly in the microwave so it will spread easily. Spread it evenly over the top center of the cake, leaving the edges clean. (The cake will have sunk a bit in the center,leaving a raised edge around the outside–spread the jam in a circle in the middle, leaving the edges alone.)

When the cake is at room temperature, cover tightly with foil and refrigerate for eight hours or overnight.

To serve, run a thin spatula or knife around the edge of the springform pan and the cake. Rub the outside of the pan with a very hot, damp towel, then spring the latch and carefully pull the sides off the pan. Set the cake with the pan bottom on your serving plate.

Just before serving, carefully sprinkle a ring of lightly crushed sliced almonds around the circle of jam, then cover the jam with fresh raspberries set in concentric circles. If you want, you can melt a few tablespoons of raspberry jam and apply it to the raspberries to make a shiny glaze after they are on the cake, but it really is only necessary to do that if you really want to feel like Martha Stewart. I don’t generally do it myself, but some people think it makes it all even prettier.

This recipe serves up to twenty people. I mean it. It makes a really big cheesecake, and most people will be plenty happy with thin slices.

Korean Barbeque: Bulgogi (With Asian Pear and a Simple, but Delectable, Salad)

I have been having a good time playing around in the kitchen with Korean flavors and recipes.

First, the kimchi–which is fermenting along very nicely, thank you, and tastes better and better every day. (I have to remember to take some to the farmer’s market tomorrow for the two farmers who grew the cabbage and the mustard greens that went into it.)

Inspired by the books Growing Up in a Korean Kitchen by Hi Soo Shin Hepinstall and Eating Korean by Cecilia Hae-Jin Lee, I decided to make authentic bulgogi, which translates as “fired beef.”

For years I had been making a bulgogi-like grilled sliced steak, marinated in lots of garlic, sesame oil, soy sauce and sugar and served wrapped in lettuce leaves, and last summer, after reading one of Sarah Gim’s posts on Slashfood, I made bulgogi burgers to much acclaim from friends and family, but I had never really ventured into the realm of the real thing.

It turns out that my faux bulgogi wasn’t too far off from the real thing. The recipe from Eating Korean was quite minimal; including a marinade containing only soy sauce, sesame oil, sugar, Korean malt syrup, garlic, salt, and black pepper, with scallions as an optional garnish.

On the other hand, the recipe in Growing Up in a Korean Kitchen was much more complex, with inclusions of rice wine, grated Asian pear, scallions, walnuts, corn syrup and sesame seeds in the marinade. The author notes that her family’s method of making bulgogi is similar to the more complex recipe from the royal kitchens, so that accounts for the added ingredients and the resulting kaleidescope of flavors.

I combined the two recipes to make my own version.

First of all, I decided to substitute nuoc mau (Vietnamese caramel sauce) for the malt or corn syrup, since I had absolutely neither of those, and only about a tablespoon of nuoc mau left to use up before making another batch. The Asian pear was an intriguing ingredient; apparently, it is used not only for its flavor and slight texture, but also for its tenderizing properties. Just by happenstance, the owner of the local Asian market had given Zak an Asian pear to try the last time he had been shopping, so there it was, sitting in my fridge, waiting to be used. Of course, I had to snack on its crisp, juicy flesh while I was shredding it to go in the marinade; needless to say, I have some more Asian pears sitting in the crisper drawer right now, for snacks or cooking. They are amazing: they have a light, honey-floral scent and a texture similar to fresh water-chestnut. And they have an icy, crystalline flavor to them that is so refreshing–it seemed almost a shame to put it on meat, but I did anyway, and am happy that I made that choice.

I had no walnuts in the house, so I went ahead and used the sesame seeds and didn’t worry about the nuts.

I also made double the amount of marinade so I could reduce some of it down with beef stock to make a glaze for the finished beef. I am sure that is not traditional, but I don’t really care–it tasted very, very good–especially with the Asian pear.

Growing Up in a Korean Kitchen also suggest three traditional salads as side dishes: radish salad, cucumber salad and leaf lettuce salad. Well, I was fresh out of radishes; they had all been used up in the kimchi making extravaganza, and I had no cucumbers. Leaf lettuce, however, had been in abundant supply at the farmer’s market, so I had bought a great pile of it. I looked at the recipe, and it seemed stunningly simple, yet all of the ingredients were tasty, so I thought–“Why not?”

How did it all turn out?

Well, we ate all of it. I am sorry the photographs turned out so lousy; the camera was acting up and then the battery died after only a few shots. I had no backup batteries in the charger, so I went with what I had, which unfortunately are not appetizing pictures. Yet, let me say, the flavors of the beef were fantastic after a brief grilling, but were even better after the reduced glaze was applied. The salad was surprisingly great; it is hard to believe that a salad that consists of so few ingredients can taste so fresh and delightful. It was a great foil for the beef.

The kimchi, as noted above, was coming along nicely, with a strong garlic top note (probably from the combination of garlic and ramps) and a tangy fizz from the fermentation, with a whiff of incendiary power from the ginger, mustard greens and chili. The rice, which was not short grained as it should have been, but long-grain jasmine, because that is what we had, was great with the glaze drizzled over it, and the bean sprouts I simply tossed with some sesame oil were crunchy and nutty.

Since the author of Eating Korean tells me that bulgogi is an integral part of bibimbap–a mixed dish of various ingredients served over rice, I think that I shall have to try that as my next Korean culinary experiment. Although I don’t think it is absolutely true that bibimbap requires bulgogi-at least the writer at Zen Kimchi doesn’t seem to think so-I still think that a beefy version of it would be quite tasty. I mean, as it was, I mixed everything on my plate into a fine and tasty mess before and during eating it as it was, so bibimbap seems to be the next logical step.

Until then, though, here is my way of making bulgogi. If you want to make a glaze to pour over the beef and rice after it is cooked, double the marinade recipe, add about 1/4 cup of beef or chicken broth or stock, and simmer over medium heat until it reduces into a thick, shiny glaze.

Ingredients:

2 pounds top round or sirloin, sliced across the grain into slices about 1/8″ thick

3 tablespoons soy sauce

1/2 cup Korean rice wine, sake or dry vermouth

1 tablespoon toasted sesame oil

2 teaspoons raw or brown sugar

1 tablespoon Korean malt syrup, corn syrup or nuoc mau

1 Asian pear, peeled and finely grated

2 scallions, white and light green parts, finely minced

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon toasted sesame seeds

1/2 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper (I left this out, alas, because of my allergy)

Korean red chile flakes to taste (for serving and as garnish)

dark green tops to 2 scallions, finely sliced (for garnish)

Method:

Mix together all ingredients from soy sauce to black pepper, and rub briskly into the beef slices. Allow beef to marinate for two hours or overnight.

Heat charcoal grill until it is quite hot, and grill meat for two minutes per side, or until done as desired, basting with any marinade left in the bowl twice while cooking. (If you put a weight to press down the beef, it will not curl. Or, thread a soaked bamboo skewer through each piece of beef before grilling to keep them laying flat.)

Remove beef from grill, and cut into bite sized pieces. Sprinkle with garnishes and serve with leaf lettuce salad, steamed rice and kimchi.

Note:

If you want to make a glaze, double the ingredients for the marinade. Use half as a marinade, and to the other half, add 1/4 cup chicken or beef stock or broth, and simmer on medium heat until it reduces to a glaze. Drizzle over the bulgogi and steamed rice is done.

Leaf Lettuce Salad

Ingredients:

1 pound leaf lettuce, washed, dried thoroughly (wrap it in kitchen towels to get it completely dry) and cut into thin ribbons

1/2 tablespoon soy sauce

1 green onion, white and pale green parts, finely minced

1 clove fresh garlic, peeled and minced

1 tablespoon sake or dry vermouth

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1/8 teaspoon anchovy paste

1 tablespoon freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 tablespoon sesame oil

1 tablespoon toasted sesame seeds

1 teaspoon Korean hot chile flakes (or to taste)

Method:

After the lettuce is sliced up, chill it thoroughly in the fridge for at least one hour.

In a small jar, mix the other ingredients, put the lid on it tightly and shake well to combine.

Just before dinner, toss thoroughly with the lettuce, and serve immediately.

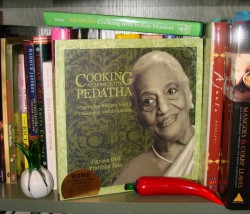

Book Review: Cooking At Home With Pedatha

“From food all creatures are produced. And all creatures that dwell on earth, by food they live, and into food they finally pass. Food is the chief among beings. Verily he obtains all good who worships the Divine as food.” –Taittiriya Upanishad

This quote is the text chosen as the opening to Jigyasa Giri and Pratibha Jain’s absolutely gorgeous, award-winning book, Cooking At Home With Pedatha: Vegetarian Recipes From a Traditional Andhra Kitchen, and it sets the tone for the entire work, which is the exploration of the soul of a cuisine through the memories and orally-transmitted recipes of one amazing woman.

Who is Pedatha?

Her name is Subhadra Krishna Rau Parigi, and she is the eighty-five year old eldest child of a former president of India.

She is known fondly among friends and family, however, by the nickname, Pedatha, which loosely translates as “eldest auntie,” and she is a font of culinary wisdom rooted deeply in her home state of Andhra Pradesh in the south of India. She also is a woman who understands innately that cooking is a deeply spiritual act which is intimate and intensely personal, yet which is so often treated as something to be taken for granted as simply impersonal “fuel” for immediate consumption and gratification without any reflection upon the holiness of the acts of cooking and eating. She is an embodiment of the philosophy of “Slow Food;” when asked by the authors how long it would take to cook a certain dish she answered, “As long as it takes for a good dish to be ready.”

While Pedatha gladly gave very precise measurements to the authors as they translated her orally transmitted recipes into book manuscript form, when pressed about timing, she would say, “Do not look at the time, look at the pan.”

A wise cook knows that she is right, of course. How long a certain dish takes to cook will depend on how and where it is cooked. How high is the heat on your stove? If it is higher than Pedatha’s, it will cook faster. If it is cooler than Pedatha’s it will take longer for the same dish to cook properly. A wise cook and reader will recognize that Pedatha’s advice, while seeming to be evasive are nothing more than a simple truth: not every bit of cookery can be measured, quantified and recorded perfectly and accurately. Cooking is not wholly a science and thus is entirely subject to the clock, the thermometer, the scale and the measuring spoon. It is also an art that is dependent upon the senses of the cook: her eyes, her nose, her hands, her ears, her mouth, to tell her when something is cooking properly.

But enough about Pedatha, already! I can hear my readers thinking this–tell us about the recipes!

Ah, but you see–the book is as much about Pedatha as it is about the recipes. The way they are written, and the way the book is put together, with lovely photographs of ingredients and finished dishes, along with evocative portraits of Pedatha’s mobile and ever-changing face–I swear, it seems as if I can hear her voice on every page. It is like having her in the kitchen with me, telling me how to temper spices, or how to tell when curry leaves are cooked enough, or what these pickles will smell like when they are done.

The recipes are detailed, and precise, for all that cooking times are fluid. The cookbook is completely vegetarian, though not vegan in orientation, as ghee and yogurt are used in many dishes. (And I have to admire Pedatha for admonishing the authors and the readers to not skimp on the ghee! She sounds very like my own Gram, who after WWII’s rationing forced her to eat margarine, would only eat butter after that, and a lot of it. And she, like Pedatha, was quite healthy, slender and pretty, well into her eighties.) Many of the dishes are highly spiced, and there is an entire chapter on the making of podi-powders, which are used to season rice and other foods. There is also a chapter on sweets, but I am more excited to try the chutneys and pickles, and the lentil and eggplant dishes. (The recipes chosen for this book reflect Pedatha’s own personal tastes, and I am happy to see that she seems to like eggplant as much as I do.)

I haven’t cooked yet from this book, but as the summer season begins to progress, bringing its delightful bounty of fresh vegetables, I intend to cook many dishes from this book as I explore and experiment with the flavors and traditions of southern India. Have no fear, I will present the recipes as I test them.

I feel as if, with Pedatha guiding me from the bookshelf and Indira of Mahanandi a keystroke away, I cannot go wrong as I take my first baby steps in learning the ways of the South Indian kitchen.

Not with two such wise and generous kitchen angels looking over my shoulder.

So, dear readers, if you are interested in learning how to cook the vegetarian foods of South India, particularly Andhra Pradesh, I urge you to pick up a copy of this book, sit down and enjoy a good, thorough reading of it. Then, go to the kitchen and start cooking. And then after you have cooked a dish or two, check in on Mahananadi for another dose of inspiration and kitchen wisdom.

You cannot go wrong.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.